Every year, we spend billions of dollars in pursuit of perfection.

Anti-aging creams for flawless skin. Supplements promising the ideal gut biome. Activity trackers aimed at securing a perfect night’s sleep. And countless apps to help us find the perfect lover, job and life. Yet, we pour billions more into pharmaceutical drugs and mental health services because, all too often, these pursuits fall short.

With results like these, you wonder, what’s the point?

One thing I know to be true about money is that no one is perfect with it. Good with it, sure, but perfect? Never. Financial skeletons dance in all of our closets. Whether rich or poor, we’re vulnerable to making mistakes.

As psychology professor and author Dan Ariely wrote:

“When it comes to money, emotions, biases, and the context can lead us astray more than we realize.”

Take splurging, for instance. We all splurge, whether it’s overspending on $300 star-studded diamond sneakers or a $600 million star-studded wedding (I can’t even imagine the feeling of opening that credit card bill…).

Think back to the last time you treated yourself. How did you feel afterward?

The coping process often unfolds like this: we experience guilt or shame, as if we’ve committed some grave sin. We knew it wasn’t the most prudent decision, yet we went ahead anyway. This sense of humiliation can weigh particularly heavily when we’re striving to achieve ambitious financial goals, like becoming debt-free or saving for retirement.

In our quest for perfection – driven by today’s relentless cultural messages – we often ask ourselves, what’s the point? This mindset can lead us to abandon our goals or to restart with the same fragile resolve, vowing to resist temptation this time, until we inevitably falter again.

Scientists, ancient philosophers and even the Terminator say we’ve got it all wrong.

The mistake isn’t in the splurge itself; it’s in the pursuit of perfection. Allowing ourselves the occasional indulgence can actually serve as an effective tool for sustained success, steering us toward greatness rather than the dead-end chase for perfection.

So, let’s explore why we splurge and how it can actually be a force for good – if not more.

If you can’t recall a splurge of your own, let me share one that inspired this post.

Splurging away in Margaritaville

I have a simple philosophy: There’s no decision in life that a margarita can’t justify.

This revelation hit me where all great ideas are born, during a long road trip with two overtired and bored kids squabbling in the backseat. We were headed to the Smoky Mountains for a camping trip, but Mother Nature had other plans. Hurricane-force winds and an encroaching wildfire shut down our campsite, forcing us to scramble for alternative accommodations for the night.

While it would have been the financially prudent choice to settle for a cheap roadside hotel with nothing but dispiriting views of a parking lot and fast-food joints, we were unwilling to waste a day and night in such a place. Instead, we set our sights on downtown Gatlinburg, where we could explore some tourist attractions and maybe even crash a bachelorette party.

My wife scrolled through hotel listings on her phone, searching from lowest to highest price, hoping to find something within our budget. But every hotel seemed booked. Meanwhile, the restless prisoners in the back protested the confines of their seatbelts, demanding a hotel with a swimming pool.

Finally, an available room popped up – in a hotel with a pool, and a bar, and even two live parrots. Technically, it wasn’t a room, it was a suite. And, figuratively, it wasn’t a hotel, it was a kind of town, a town named after a beverage. And spiritually, it wasn’t even that, it was a state of mind – Margaritaville.

Yet, the idea of spending more than three times the amount we would pay for an entire week at the campsite for a single night in a brightly colored, tropical-themed resort dedicated to Jimmy Buffett seemed like something someone who had one too many margaritas would do.

And yet, after hours of driving and with the pressure to find lodging, we longed for anything to lift our spirits.

And yet again, what the hell? We were on vacation.

A margarita does sound pretty good right about now, I thought. Except I actually said it out loud. Yes, yes, it does, my wife agreed.

A couple of hours later, I handed my credit card to the mayor of Margaritaville – who might have just been the concierge – then squeezed and dropped a fresh lime wedge into a salt-rimmed margarita on the rocks. As that green fruit canoe sank into the depths of Blanco tequila, so did my worries about the cost.

You can only learn certain truths about your relationship with money through experience. At that moment, I realized I’m the type of person who willingly splurges on vacation. At home, I’m consistently cost-conscious, fretting over every dollar. But on the road, it feels like the bank truck is parked unattended with the doors wide open. You could probably make a drinking game out of how often I remark, “Well, we are on vacation.”

Since then, I’ve been curious about why we tend to splurge, even when we know the consequences. What I’ve learned is that splurging isn’t a behavioral defect; it’s an emotional release valve. Paradoxically, it can help you embrace the discipline needed to become better at whatever you’re striving for.

Hence, my facetious motto: There’s no decision in life that a margarita can’t justify. It serves as a personal reminder that it’s okay to choose to do imperfect things. Just grab yourself a margarita and forget about it; you’ll be fine.

The truth is, most of us splurge not because we lack financial discipline or are inherently bad with money, but as a response to our situation or emotional state – often mounting stress that tips the scales of our sanity, like the misadventures of a long drive with young kids.

The root of our desire to splurge

The NBC producer Don Ohlmeyer once said:

“The answer to all your questions is money.”

But when it comes to questions about money, the answer is almost always “emotions.”

Why do people primarily splurge? Emotions.

A study from the University of Michigan reveals that overspending is not merely a “lapse in financial judgment.” Instead, psychological forces are at play. Splurging serves as a temporary distraction from stress or emotional pain. So-called “retail therapy” is real, with shopping shown to enhance feelings of personal control and alleviate sadness.

Additional research indicates that splurging is a multi-dimensional behavior influenced by various factors. For example, the “bandwagon effect” – adopting behaviors because others are doing so – can lead us to splurge on material goods as a form of social proof.

However, splurging goes beyond simply buying “stuff.” Some researchers argue that we’re motivated to splurge because we seek peak experiences – driving the fastest car, sipping the finest whiskey, or staying in a five-star hotel (maybe even one with parrots).

Ultimately, the main reason we splurge may boil down to one thing. A Deloitte study found that the desire to treat ourselves transcends cultures worldwide. This isn’t just a defect of consumerist societies like the U.S. More than 75% of consumers surveyed globally reported making a splurge purchase in the past month, despite only 42% claiming they could afford it.

What makes this study particularly compelling is the primary reason people give for their splurging. The authors write, “Across all our categories, more consumers tell us they seek comfort and relaxation (i.e., stress relief).” The “one constant is that consumers generally relieve the pressures of frugality by occasionally treating themselves.”

The key word here is pressure. Simply put, people often place themselves under pressure to be frugal. Eventually, that pressure builds up, and they need a way to relieve it.

The same dynamic applies to our efforts to improve ourselves.

Few things are more gratifying than pursuing significant goals or developing better habits, which inherently require us to apply some pressure. Yet, too much pressure for too long – especially the pressure to be productive, optimize our time and strive for perfection – can lead to anxiety, exhaustion and, ultimately, burnout.

Worse still, some individuals may begin to view joy with suspicion, irrationally believing that if they aren’t suffering under pressure, they’re doing something wrong. As the classic Queen/Bowie song goes: “Insanity laughs under pressure.”

Long before that, the Greek philosopher Seneca warned against an unyielding pursuit of excellence:

“It is inevitable that life will be not just very short but very miserable for those who acquire by great toil what they must keep by greater toil. They achieve what they want laboriously; they possess what they have achieved anxiously; and meanwhile they take no account of time that will never more return. New preoccupations take the place of the old, hope excites more hope and ambition more ambition. They do not look for an end to their misery, but simply change the reason for it.”

Essentially, the very process you initiate to achieve specific goals or solve certain problems can become a problem in itself – the cure becomes the poison.

So, if the pursuit of ambitious goals only leads to misery, what’s the point?

The solution seems to lie in relieving some of that pressure, even if it means occasionally indulging in things you feel you shouldn’t be doing.

This applies even when you’re striving for significant transformations, like turning yourself into a Greek god.

Mr. Olympia splurges on pie

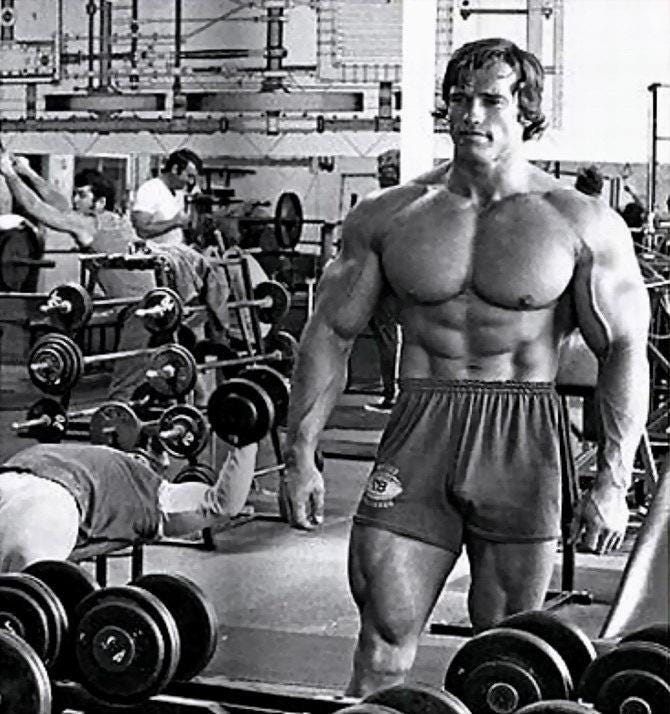

During his decorated bodybuilding years in the 1960s and 70s, Arnold Schwarzenegger won seven Mr. Olympia titles and four Mr. Universe crowns. His legendary lifting routines are still discussed in the fitness community today.

What’s less talked about is what happened during the future Conan’s particularly grueling training schedules. Sometimes, he and fellow competitor Franco Columbu were found not in a hot, muggy Spartan gym demolishing weights, but rather among the clatter of plates and silverware, with the enticing aromas of cinnamon, vanilla, and sugar wafting through the air as they demolished pies.

In a Reddit post, Schwarzenegger explained:

“What normally happened with the pies was we would be dieting down, before a competition, and we would go splurge… We were depriving ourselves every day, and eventually, Franco and I would snap, and we would end up at the House of Pies in Santa Monica.”

You can’t look at those two men and think they lacked willpower or work ethic. Their pie splurges reveal a fundamental truth about human behavior regarding dedication to goals. Setting strict, unrealistic restrictions often backfires.

The more restrictive the approach or the greater the pressure to be perfect, the less likely one is to succeed.

Research shows that highly restrictive diets generally don’t work. In fact, they can have the opposite effect. It’s been found that 95% of dieters regain the weight they lost within two years. A review of over 30 long-term studies indicates that dieting can actually lead to weight gain; the more diets someone has tried, the more they tend to weigh.

Even worse, restrictive dieting can create a negative relationship with food, leading some individuals to develop severe eating disorders.

What often happens is that we give in a little, then think, “Since I’ve gone this far, I might as well go all the way,” ultimately falling off the wagon. Alternatively, we may feel enough shame to believe we’re simply not up to the task. Either way, we quit.

This pattern characterizes why people abandon their dreams, whether it’s writing novels, starting businesses, pursuing desired professions, running marathons, you name it. It’s as if we lack the ability to forgive ourselves for not being perfect.

It illustrates that striving for perfection is a losing proposition. This notion seems counterintuitive when we often hear about the superiority of certain individuals. However, when you peel back the stories and look at the whole picture, the truth is much different.

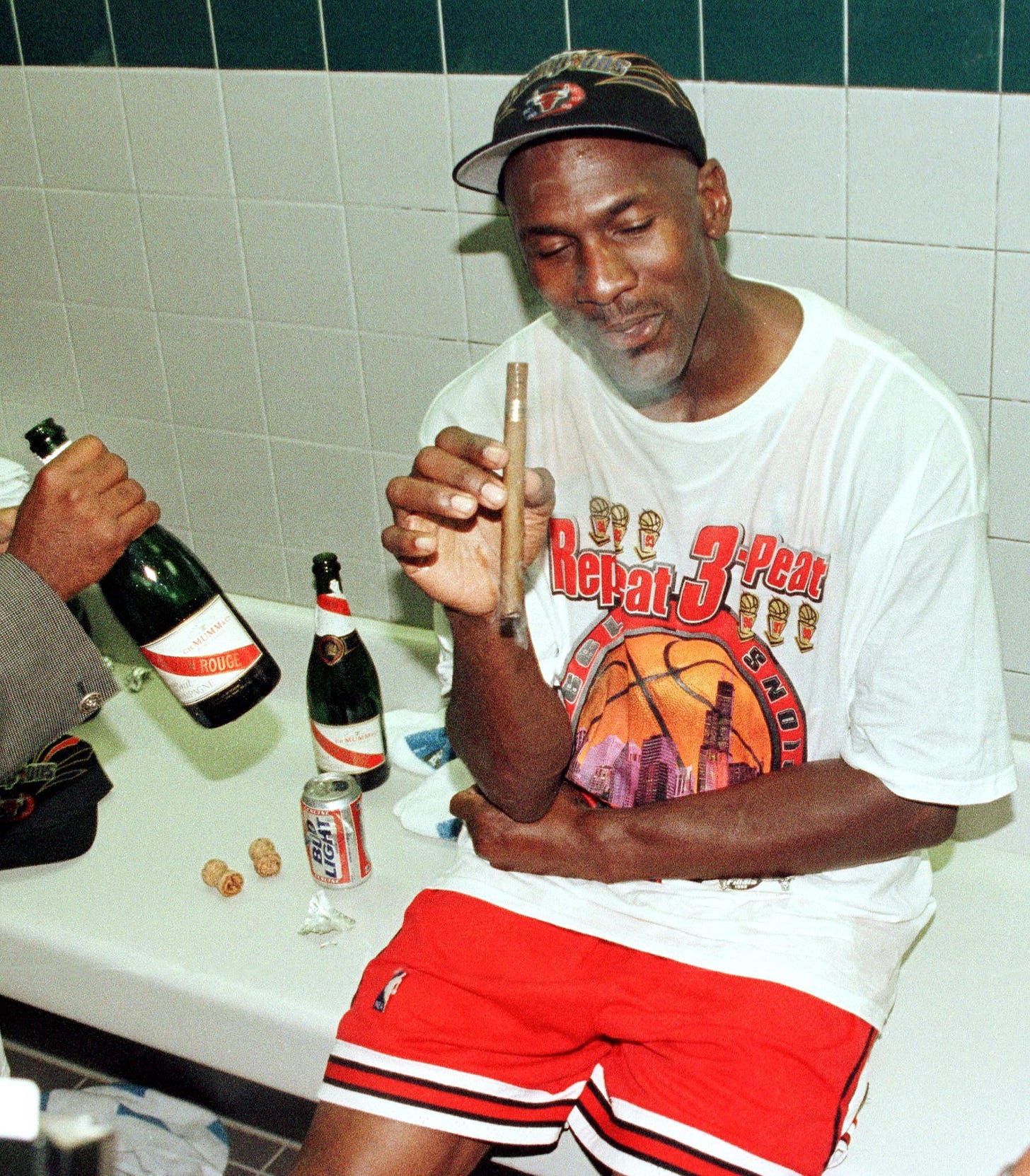

Take Michael Jordan, for example. Known as the greatest of all time, he was characterized by an uncompromising and tyrannical work ethic and attitude toward himself and his teammates. Yet, he was also known for his indulgences off the basketball court: smoking cigars, drinking whiskey and, most notoriously, gambling.

The common thread among the greats – like Jordan and Schwarzenegger – is that they are great, not perfect. They make time for things that aren’t necessarily healthy or productive for their goals. They push the limits in what they do or achieve, but they also know when to back off, allowing them to hit those high marks again.

If the greatest in their profession aren’t perfect, what does that tell you about perfection?

It suggests that those imperfections may contribute to greatness, resonating with the core tenet of the Japanese philosophy of Wabi-Sabi.

Wabi-Sabi celebrates the beauty of imperfection. It’s often described as appreciating beauty that is “imperfect, impermanent and incomplete” in nature. Everything is in flux and, therefore, never complete, never perfect. Perfection doesn’t exist.

This philosophy encourages you to appreciate the journey and your evolving progress over time. An old, faded piece of Japanese pottery with cracks is celebrated for the elegant simplicity it has attained through decades or centuries of existence. This stands in stark contrast to typical Western mentalities that constantly chase newness and idealized, mass-produced visions of perfection, which prove unfulfilling.

Ultimately, it’s the pursuit of greatness rather than the lost cause of perfection. It’s not about being perfect – which is an illusion – but about getting a little better day by day.

You can’t deprive yourself of joy in life and call it perfection.

Consistency trumps perfection every time.

Schwarzenegger put it this way:

“You should mostly eat food you know is healthy. There is no magic food.

You should also occasionally let yourself eat delicious food you know isn’t healthy. Otherwise, what’s the point?”

Cheat to be great

Schwarzenegger’s 1970s pie-filled splurges now have a common name: cheat days.

I’d argue that it’s a bit of a misnomer. When done intentionally, you’re not cheating; you’re helping yourself.

Nutrition experts say that incorporating periodic cheat days can help people on highly restrictive, low-calorie diets stay on track, allowing them to eat better throughout the week. There’s even evidence that your metabolism rises after a cheat meal, causing you to burn calories faster.

Essentially, a planned splurge in calories can fortify people against unplanned, binge-inducing meals that are hard to recover from and often lead to quitting or reverting back to square one.

Therefore, cheat days, or splurges, help you maintain a high level of consistency most of the time. It may not be perfect, but it’s effective. It’s a process you can repeat, whereas striving for perfection is a one-way road to burning out. This is the path that the likes of Schwarzenegger and Jordan take to achieve greatness.

Kevin Kelly, writer and founding editor of Wired magazine, put it succinctly:

Recipe for greatness: Become just a teeny bit better than you were last year. Repeat every year.

When driving over hard, rugged terrain, it’s customary to release some pressure in your tires. We should do the same for ourselves. Essentially, splurging every once in a while allows you to control the pressure valve, reinforcing your commitment to whatever goal you’re chasing. A better way to frame it might be “cashing in some chips.” You’re taking a portion of the rewards from the bigger pot you’ve earned, helping to keep you in the game.

With money, what’s rational isn’t always reasonable. Setting a strict budget can make people feel miserable unless they see a deeper purpose in living a frugal lifestyle. That’s why, to stick with a goal – such as paying off debt or hitting a savings target – financial experts often recommend rewarding yourself.

When done within one’s means, splurging can be a healthy expression of personal financial management, allowing for enjoyment without compromising financial security.

If you can’t spend money just for the joy of it every once in a while, then what’s the point?

And if you feel hesitant, here’s a bit of advice: get yourself a margarita and forget about it.

“There is a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in.” - Leonard Cohen