Our Complicated Relationship with “Stuff”

What to know about the good and bad of our attachment to possessions through some of my own

Steve Jobs will be remembered for many things, but not all of them he had a hand in designing.

Picture him in your mind, and you’ll likely picture this:

Along with the Mac and iPhone, Steve Jobs helped make the black turtleneck iconic as his daily uniform. He supposedly owned 100 of them. We can play this object-association game with all sorts of famous people. Take, for example, a smoking pipe (Albert Einstein, Mark Twain) or a cone bra (Madonna).

It seems absurd to reduce the essence of storied thinkers and artists down to inanimate objects. Isn’t a turtleneck just a turtleneck? Not to our meaning-seeking brains. Our tendency to connect material goods to people, places or even other things reveals an important aspect of our often messy relationship with “stuff”.

Many personal finance and wellness experts argue that material possessions won’t bring happiness, suggesting that spending on experiences is more valuable than acquiring stuff. While there’s a lot of truth to this perspective, it doesn’t capture the full story.

This viewpoint fails to consider the deep psychological bonds we form with our possessions, known as psychological ownership. This concept describes how we see our belongings as extensions of ourselves, highlighting a more nuanced relationship with the things we own.

The psychologist William James argued that our possessions define who we are:

“Between what a man calls me and what he simply calls mine, the line is difficult to draw.”

Indeed, research reveals our relationship with stuff is complicated, going beyond “keeping up with the Joneses” or the thrill of the latest purchase. Our attachment to items like Steve Jobs’s turtleneck shows we form deep connections with objects that transcend social status or fleeting happiness.

Recognizing our own emotional ties to items helps us to foster a healthy relationship with our belongings, grounded in mindfulness rather than mindless accumulation. It can be a continuous journey.

To illustrate, and for fun, let’s explore my personal experiences and feelings toward some of my own stuff.

Stuff isn’t just stuff

I remember stepping out into the garage to cry alone, wiping away tears with the sleeve of a black suit I bought two days before just for the occasion. A few minutes later, my mother joined me. We stood silently in our grief among lawn equipment and sporting goods.

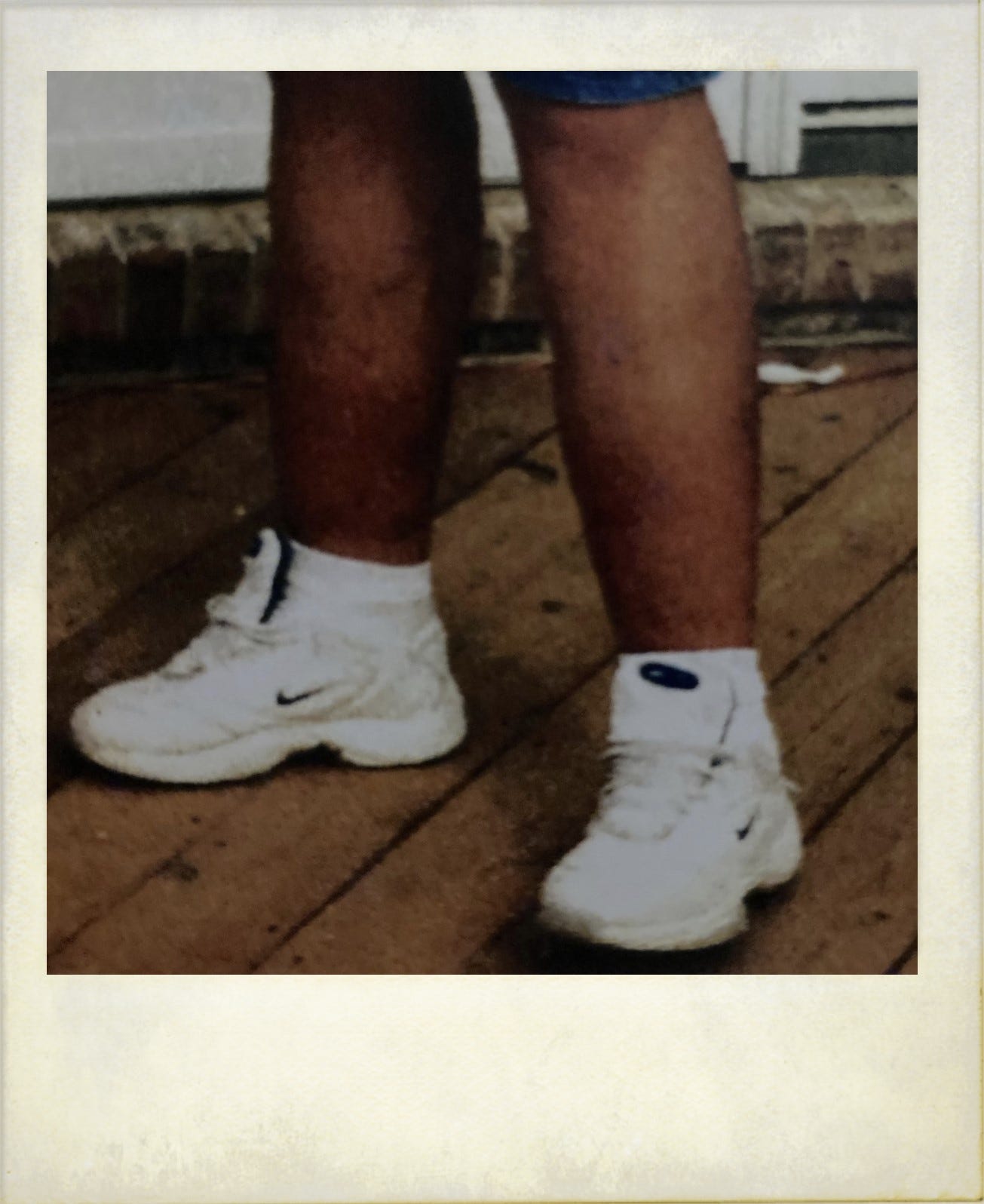

Then she broke the silence while putting her hand on something on a shelf. “His shoes,” she said.

They were the kind of bulky white sneakers worn by middle-aged men across the country. Looking at this pair, we both started sobbing.

Plenty of research shows that we have strong emotional and psychological attachments to material things. Objects offer reliability, control and comfort, often using them as emotional substitutes when human relationships are lacking or unstable.

As infants and children, we may use objects as substitutes for our mothers’ presence, like a security blanket, pacifier or, in my case, a stuffed monkey named Billy.

Essentially, we see objects as an extension of ourselves or others. We believe objects are suffused by our very essence or that of others. This is darkly evidenced by our strong reactions to items with negative associations, like Nazi memorabilia or a serial killer’s aviator glasses.

So, what my mother said, “his shoes,” wasn’t a statement, it was a story. A story of the man who owned them, who wore a size 13, a man who had been 6’8” and dominated on the basketball court in his youth, a man who made a living with his hands, a man who brought a lot of love and laughter to the world, a man we were mourning at his home after his funeral.

They weren’t just shoes; they were my Dad’s shoes.

Stuff isn’t just stuff.

It’s been said the average American home has anywhere from 10,000 to 50,000 items. Sure, that’s probably much more than we need. But look around and consider the meaning of every item, chances are you’ll likely see a lot more than just stuff.

Stuff is our means of time travel

Recently, my wife cleared out our kids’ closets of old clothes. But what started as an overdue chore became something more profound. Sorting through the piles designated for keepsakes or donations, I found myself immersed in a mental home movie.

These clothes were more than just fabric. They held memories, like a first thrilling visit to Hockeytown, USA:

Our belongings are our personal time machines. A paper published by the Association of Consumer Research indicates that material items play a key role in helping us construct and preserve our sense of the past.

The author concludes:

“Possessions can be a rich repository of our past and act as stimuli for intentional as well as unintentional recollections… We fervently believe that our past is accumulated somewhere among the material artifacts our lives have touched--in our homes, our museums, and our cities. And we hope that if these objects can only be made to reveal their secrets, they will reveal the meanings and mystery of ourselves and our lives.”

This sensation makes it challenging to part with heirlooms or personal items like old report cards.

Essentially, material objects allow us to explore not just space but also time, even fueling nostalgia for a past we’ve never experienced through collections of vintage cameras, records or typewriters.

Moreover, certain possessions mark life’s milestones, such as your first car, home, or stroller. Whether right or wrong, these items have become modern rites of passage.

In essence, our belongings make the abstract tangible, serving as anchors to our past lives or stepping stones toward our future aspirations.

Actually, buying stuff can make you happy

While I might not strictly need a truck, I was happy the day I bought it and it has undeniably brought me immense joy ever since, guiding me through campsites across Michigan and into the Smoky Mountains.

There’s a growing trend to prioritize experiences over things, believing they offer more lasting happiness. However, this isn’t always the case.

In a 2015 study, researchers from the University of British Columbia found material purchases provide more long-lasting happiness than experiences, challenging the common belief that experiences always trump material goods in contributing to long-term happiness.

Additional research suggests that spending money on material things can indeed contribute to happiness, particularly when they align with your personality or facilitate valuable experiences.

For instance, a 2014 study found that products facilitating experiences, such as bicycles or books – or trucks – can provide as much happiness as life experiences.

It’s what author and UNLV professor Michael Easter defines as “gear” rather than stuff:

“Gear is a tool we can use to have better experiences that make us healthier and give our lives meaning.”

This indicates that objects enabling creativity, enhancing experiences, or fostering connections can significantly contribute to happiness – and possibly more.

Some stuff can boost your confidence

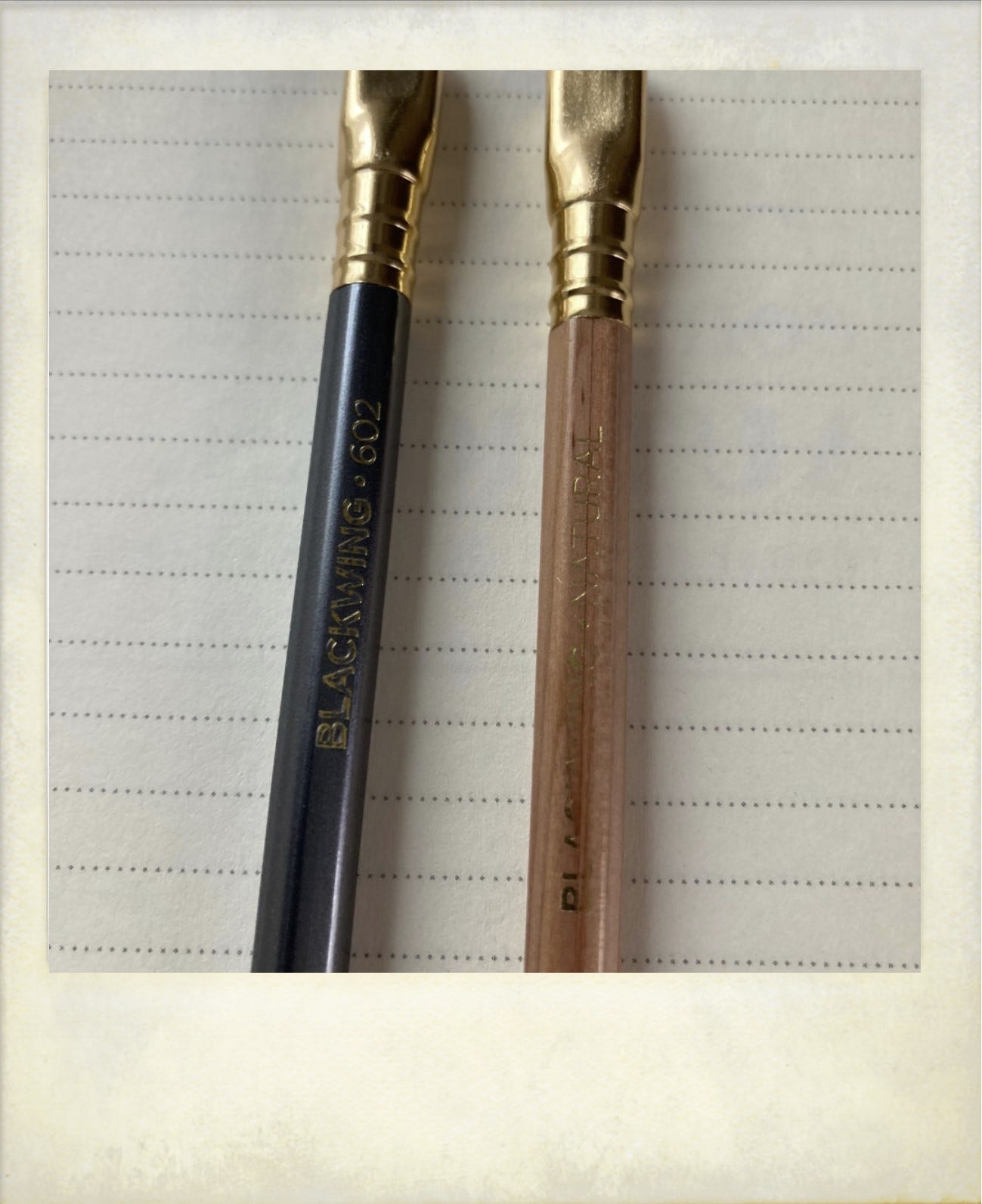

Thor has Mjölnir; I have Blackwing. Well, a Blackwing pencil. I could write with any kind of pencil, but the words seem to flow better with this kind in my hand:

It might seem superficial, but we all have favorite tools – be it pens, notebooks, laptops or wrenches – that genuinely make us feel good. This feeling isn’t just in our heads.

Our possessions can improve our beliefs about our abilities. According to a Northwestern University study, the feeling of psychological ownership can raise our self-esteem, which in turn increases our drive to help others.

Study author and professor Ata Jami explained:

“Regardless of your overall trait level of self-esteem, ownership can actually give you a temporary boost in your self-esteem.”

So, to keep the superhero metaphor going: Much like Batman’s utility belt, material possessions can endow us with what feels like special abilities.

However, echoing Spider-Man’s wisdom, with great power comes great responsibility. We must be cautious of the influence these possessions can exert over us.

My stuff, your s**t: It’s a matter of perspective

What do you think this bike is worth?

I bought it from an elderly neighbor for $50. It rides like a Cadillac, and if I were to sell it, I’d ask for more. Being familiar with behavioral finance, I know the value I place on it is only partly related to its quality. The rest is my ego projecting that I’m kind of a big deal.

The comedian George Carlin had a famous bit about stuff, where he asks:

“Have you noticed that their stuff is shit and your shit is stuff?”

It’s the best description I’ve ever heard of the mental bias known as the “endowment effect.” This is the tendency to overvalue the things we own more highly than we would if they did not belong to us.

We think our stuff is awesome because, obviously, we’re awesome.

Scientists have been even able to see the endowment effect in action, as a 2022 study in Nature Human Behaviour used brain imaging to show that the act of ownership activates brain regions associated with reward and value, even for trivial objects.

This helps explain why decluttering can be so emotionally challenging.

Marketers and salespeople use the endowment effect as a psychological trick to boost sales by making consumers feel a sense of ownership toward a product, leading them to pay more. For example, test-driving a car is designed to foster this feeling, making it harder to resist buying.

An awareness of this bias – that is, knowing the impact interacting with material objects can have on us – can potentially help us avoid overspending and foster a more mindful relationship with our possessions.

Because one pitfall of stuff is losing sight of exactly who owns whom. As Ralph Waldo Emerson observed:

“Things own the man who serves them.”

Drowning in our own stuff

I’m not a Stephen King fan. I’ve just been unable to get into his work… just as I’ve been unable to relieve myself of this Stephen King book:

What’s worse, I have many more like it. Books I didn’t enjoy or never plan to read again but still keep under the false belief I may need them one day.

This is one behavior of a hoarder.

Most of us like to keep sentimental items, but cherishing our things becomes a pathological condition – it’s been estimated that around 4% of adults exhibit hoarding behaviors – when people can’t stop collecting stuff and can’t throw anything away, no matter its usefulness or value. Even if it harms their health, life and relationships.

Thankfully, my inability to rid myself of things doesn’t venture beyond books. Most of us likely fall somewhere on the hoarding spectrum. I mean, there are now more self-storage facilities in the U.S. than McDonald’s, Burger Kings, Starbucks and Walmarts combined.

At the very least, we struggle with the art of letting go. Instead of downsizing our closets, we make them larger and fill them with more clothes.

Research from the University of Virginia suggests when attempting to make changes, we have a natural tendency to add rather than subtract. When faced with problems, our initial instinct is to introduce new elements, believing that more features or rules will enhance the outcome. However, this research indicates that subtraction often leads to better results.

This suggests, in both our possessions and our lives, the secret to valuing what truly matters may lie in having less, not more. Take it from the 13th-century mystic Meister Eckhart:

“The soul grows by subtraction, not addition.”

Is less stuff the secret to happiness?

I wrote of my late father’s shoes. What about my own? These are my running shoes (Brooks Ghost forever!):

They are not the purpose, they serve the purpose: health and challenge, fun and discipline, hope and failure, serenity and suffering, and, ultimately, an ineffable feeling of connection to the world around me. I burn through one pair at a time over road and trail, through heat and snow, during jog or race. One pair for all my needs.

Having enough in proportion to your needs, nothing in excess, is a principle of Benedictine monks – and maybe the secret to a happy relationship with stuff.

Monks, who take a voluntary vow of poverty, typically own nothing – no bank accounts, no cars, no property. They often don’t even own many personal items like books. Everything is communal.

That may sound harsh. Yet, various studies have found that Buddhist and Christian monks and nuns exhibit higher levels of happiness and satisfaction than the rest of us, non-monastic, materialists. They lead a simple life with minimal possessions, which seems to reduce the stress and dissatisfaction associated with materialism.

Saint Mother Theresa, known for her missionary work with the poor in India, put it succinctly:

“The more you have, the more you are occupied. The less you have, the more free you are.”

She seems to have spoken the truth. In fact, research suggests that materialistic people are less happy: they experience fewer positive emotions, are less satisfied with life, and suffer higher levels of anxiety, depression and substance abuse. Whew!

We have an innate thirst for meaning, searching for it in various aspects of our lives, whether it’s the meaning of money, work, possessions, power, or life itself. This quest for understanding is a persistent urge. It echoes St. Augustine’s sentiment that “our hearts are restless.” It aligns with “samudaya,” the second of Buddhism’s Four Noble Truths, which translates to “arising” and identifies the source of suffering or dissatisfaction.

Monks and nuns channel this restless energy toward a higher purpose and meaning, with transcendence serving as their center of gravity. This focus leaves little space for anything else.

The lesson here is not that happiness lies in the mere act of decluttering, but in understanding what truly gives our lives deep, meaningful purpose. Material possessions may either complement this purpose or detract from it. The issue arises when possessions become our primary source of meaning.

Therefore, having a healthy relationship with possessions is not about having more or less. This is evident in the lives of avid outdoor enthusiasts I know, who own literal barns filled with gear.

I think a good critique of our material culture isn’t necessarily that we have too much stuff, it’s that we have too little meaning.

Victor Frankl’s words resonate deeply in this context:

“Ever more people today have the means to live, but no meaning to live for.”

That’s good stuff.

PROGRAMMING NOTE:

If you enjoyed this and would like to read more posts like this, please subscribe or share it, and let me know what you think in the comments or by sending me a message: rootofall@substack.com

Much obliged!

Great piece!