You Contain Multitudes, Diversify Accordingly

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large. I contain multitudes.)

- Walt Whitman, “Song of Myself”

The world asks us to be quickly readable, but the thing about human beings is that we are more than one thing. We are multiple selves. We are massively contradictory.

- Ali Smith

A group of economists analyzed trades made by 783 elite investors over a period of around 16 years. These were investors who managed the assets of billionaires and large institutions, with an average portfolio size of $600 million. The performance of these big league investors was compared to the performance of what amounts to someone or some creature like, say, a dart-throwing monkey, randomly choosing from a list of stocks to buy or sell.

Here’s what they found: when buying stocks, these kings of finance (the elite investors) far outperformed that dart-throwing monkey. But a curious thing happened when selling stocks. The king of the treetops (the dart-throwing monkey) outperformed, as the stocks the elite investors chose to sell did better than those they chose to keep.

How could elite investors succeed on one side of a trade but fail on the other?

The economists concluded these elite investors took their time and were highly deliberate when deciding what stocks to buy. Meanwhile, they tended to make reflexive, instinctual decisions when choosing what stocks to sell. It is a real-life example of Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky’s dual modes of thought -- System 1 (quick, automatic, emotional) and System 2 (slow, deliberate, logical) -- popularized by the book, Thinking Fast and Slow. The elite investors used their galaxy brains (System 2) on one side of trade and their lizard brains on the other (System 1).

Research has proven the poet Walt Whitman right: we contain multitudes. We are vessels of contradictory desires, perspectives and emotions. We are subject to a variety of cognitive biases. In a sense, we are made up of different self states. And this consortium of selves can trip us up when making decisions, from what we order at a restaurant, to what career we pursue, to how we invest money.

Every individual investment decision, each time you buy or sell, is subject to a multitude of mental forces.

This is why it’s better for most of us, who are saving and investing to achieve financial independence, to take the don’t-put-all-your-eggs-in-one-basket approach known as diversification.

Portfolio diversification -- owning a broad mix of asset classes -- can help lower overall investment risk without dramatically sacrificing return. At least, that’s what people generally know about diversification. But that’s not what I want to concentrate on here. What I find just as remarkable, and often overlooked, is how diversification works as a mental tool.

As the study of elite investors shows, human psychology is not easily separated from money, even when you’re paid to do just that.

Diversifying your portfolio not only helps you manage investment risk, but also manage yourself/selves. You reduce the chances of making bad decisions. Essentially, you can dilute the influence of conflicting modes of thinking by owning a variety of different assets. Put simply: We contain multitudes, so we should invest in multitudes.

Here are three psychological reasons why:

When diversified, you are detached from the powers of greed and fear

If financial markets are driven by greed and fear, which wins today or tomorrow? Will markets rise or fall? Is it better to guess, or to simply not care?

Greed and fear are most acute among individual stocks, as evidenced by higher volatility. There are near daily events that impact specific companies or industries, to which investors emotionally react. Diversifying your portfolio is a way to sidestep those emotions.

Think of it this way: If you’re going to own a bit of everything, you can expect your winners to effectively make up for your losers. You are not seeking to buy more of what is rising, nor hurrying to sell what is falling. Instead, you trust the growth of the world financial markets and the law of averages will continue their gradual upward trajectory.

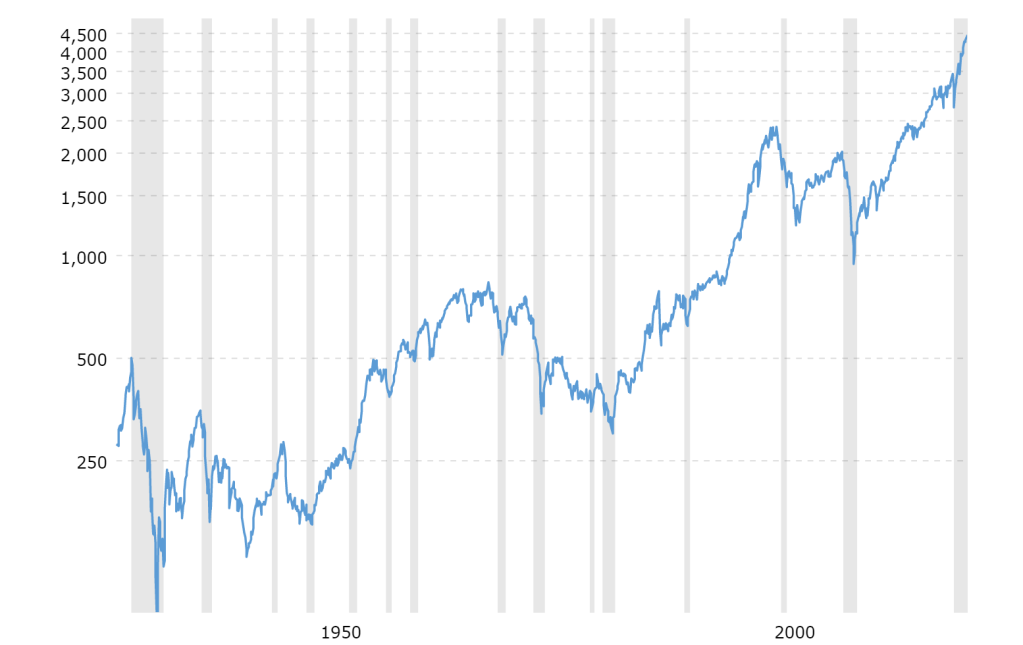

Therefore, the short-term market changes don’t matter much. Remember, throughout history, the stock market has drawn straight with crooked lines.

S&P 500 Index - 90 Year Historical Chart

SOURCE: MacroTrends

Diversification helps blunt the impact of cognitive biases

As the Novel Investor’s quilt of asset class returns show, last year’s best performing assets can often become next year’s worst, and vice versa.

From that 30,000-foot perspective, it’s easy to see betting on a specific asset class is basically a crapshoot. But in the moment, we may experience something different. For one, when deciding where to invest, we may rely on past performance. We may think recent investment trends will influence future performance, a belief known as the gambler’s fallacy. Or, we may fall prey to confirmation bias and look only for evidence that supports the investment decisions we’ve already made.

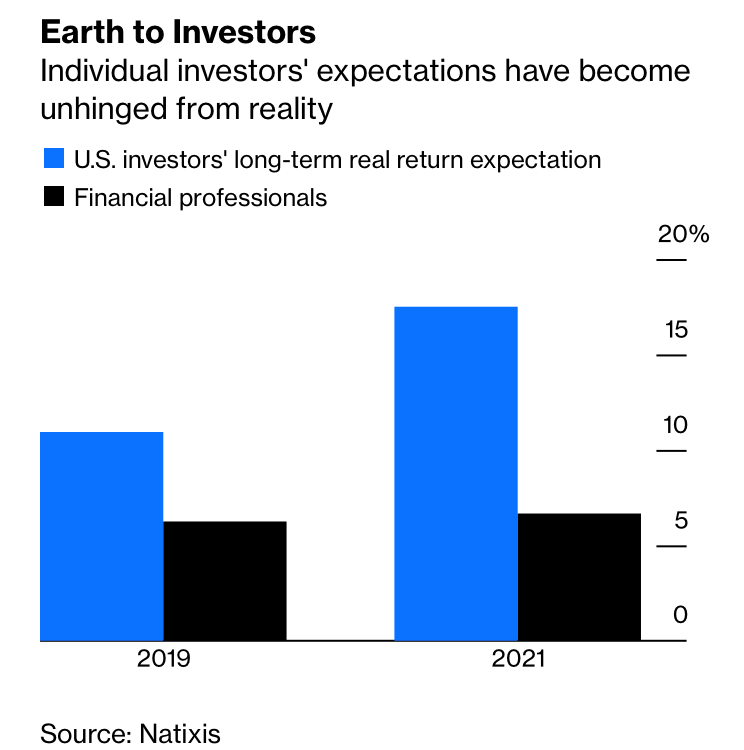

Or, at the behest of every financial news story and our Uber driver, we may succumb to herd mentality. When markets consistently hit all-time highs and you read about people becoming millionaires on meme stocks or digital coins with canine mascots, it’s understandable to come away with irrational expectations.

As Nir Kaissar wrote in a Bloomberg column, a survey found that “U.S. investors expect their portfolios to generate a long-term return of 17.5% a year after inflation”. That far surpasses the expectations of professionals:

That is unrealistic over the long term. His suggestion, of course, is to dispel any notions of anything going to the moon and to temper those outsized expectations by diversifying your portfolio.

The way I see diversification is that it is a cognitive bias silencer and the ultimate form of investor humility. It is not the path to the highest returns, which is the point. The greater the heights, the greater the fall. You don’t know what’s going to happen anymore than the next person.

Diversify, and you’ll never fall in love with the status quo

A famous though dubious quote from Henry Ford goes, “If I had asked the people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.”

By our nature, we are resistant to change. We prefer the safety of the familiar. Which is not necessarily an ideal mindset for an investor, because the fortunes of companies and countries change all the time. If you stick with the rivers and the lakes you’re used to (high five to those who got the song reference!), you may get stuck.

You could argue that Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger made a colossal mistake waiting to invest in technology. They shied away from investing in technology for a long time because it was something they didn’t understand, as it was outside their “circle of competence.”

But, who can really say what is today’s Kmart and tomorrow’s Tesla? Just look at how the top 10 companies in the S&P 500 changed from 1980 to 2020:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kfMFDcuDKYA

Rather than sticking with what you know, diversification practically forces you to own -- and reap the benefits of -- the disruptors that evolve and grow, overtaking the old guard.

Our contradictions don’t have to rule over our money. Diversification is one way to help become unhindered by our mental flaws. And there’s nothing wrong with admitting our judgments can be flawed. It’s what allows us to find ways to make better decisions.

If you believe you are not susceptible to cognitive imperfections, let Walt Whitman ask:

“Have you no thought, O dreamer, that it may be all maya, illusion?”