The Tao of Yvon

16 timeless lessons on life, money and purpose from the Patagonia founder, climber, angler, surfer (never businessman)

It takes a special person to change the way you look at the risk of death.

Legendary anchorman Tom Brokaw found this out while learning how to ice climb.

It was a dangerous place to try a new activity. Rising to more than 14,000 feet, Mt. Rainier is the most glaciated peak in the lower 48 states. Climbers face the threat of avalanches, dangerously icy terrain, and blinding snow storms. Since 1897, at least 400 people have lost their lives on the mountain.

Brokaw and his party encountered a particularly steep patch of ice at one point of the trek. One wrong move could send them plummeting 1,000 feet, so Brokaw suggested that he and a fellow climber tie up.

The fellow climber bluntly yet artfully responded: “No way – if you go, then I go, and I don’t want to do that. This is like catching a taxi in New York on a rainy day: it’s every man for himself.”

In certain aspects of life, especially those involving risk, our decisions can have serious consequences not only for ourselves but also for those tied to us.

Reflecting on that moment atop Mt. Rainier, teasing death, Brokaw said of the fellow climber, “It’s been helpful to me to be Yvon’s friend… He makes me think about things in new ways.”

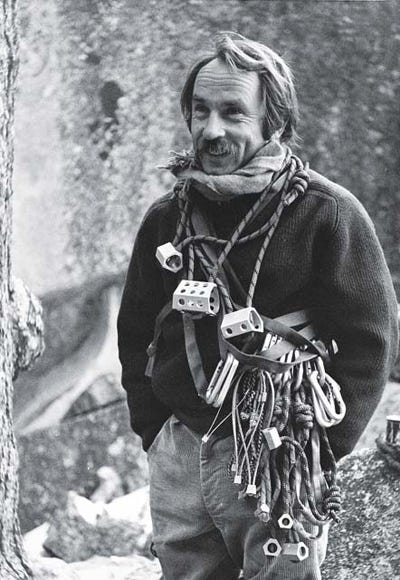

He was speaking of Yvon Chouinard, founder of the clothing brand Patagonia, whose experiences adventuring and building a business offer many lessons on living an authentic and meaningful life.

Recently, I wrote a Kiplinger article on books to read to prepare for retirement. I received much positive feedback, with requests for additional book recommendations.

Request granted: This post offers what I think are the key takeaways from another book I recommend reading, whether you’re starting out in your career or you’re long into your next chapter.

My reading list seemed to resonate because it is somewhat unconventional. Two books are novels, and only one is related to money. Even then, that book deals more with spending money than accumulating it.

I think when it comes to the subject of personal growth, the best kind of books to read are fiction and narrative non-fiction. After all, stories do a better job of motivating us to change our behavior than data. Put another way, the best lessons come from a well-lived life, not a well-plotted graph.

That’s why I recommend reading Yvon Chouinard’s excellent memoir, Let My People Go Surfing.

Supposedly, what people say they regret most while on their deathbed is: “I wish I’d had the courage to live a life true to myself, not the life others expected of me.”

Yvon has certainly done that. He even labels himself a “delinquent,” having created one of the most successful brands of the last 50 years, despite his best efforts to go climbing or fishing instead.

In the spirit of living a life true to yourself, I’ve collected 16 timeless lessons inspired by Yvon’s words that can help anyone think about life in new ways.

Apply your passions to all you do

“I and the other contrarian employees of Patagonia have taken lessons learned from… sports, from nature, and our alternative lifestyle, and applied them to running a company.”

Yvon lived and worked by the ethos of his pursuits, a winning formula for building a successful company he was proud of, a company with an estimated value of $3 billion.

This underscores the significance of staying true to your passions and values. After all, what value does a career or life hold if it’s disconnected from what brings you joy?

Every moment of your time and every decision about how you use your energy and money is a declaration of what truly matters to you.

Good comes from doing good

“Our intent is to remain a closely held private company, so we can continue to focus on our bottom line: doing good.”

“Evil doesn’t have to be an overt act; it can be merely the absence of good. If you have the ability, the resources, and the opportunity to do good and you do nothing, that can be evil.”

With its mission to “save our home planet,” Patagonia’s dedication to environmental conservation and ethical manufacturing has fostered a strong, loyal community around the brand.

Doing good can be profitable in business and life.

In fact, research suggests spending money on others makes us happier than spending money on ourselves.

Almost paradoxically, if you want more good in your life, do more good for others.

Be blasphemous: Play by your own rules

“Patagonia clothing… moved beyond bland-looking to blasphemous. And it worked.”

“I learned at an early age that it’s better to invent your own game; then you can always be a winner.”

Patagonia would have been just another clothing brand, probably long forgotten, if Yvon had been like any other founder.

Measure your life against others or try to live up to another person’s ideals, and you’ll never win.

It’s better to be blasphemous to others than be a perpetual runner-up in a race you don’t want to run.

You get to decide what winning looks like.

As Harvard professor and author Clayton Christensen wrote in his classic book, How Will You Measure Your Life?: “[I]f the decisions you make about where you invest your blood, sweat, and tears are not consistent with the person you aspire to be, you’ll never become that person.”

Know who you are

“I had always avoided thinking of myself as a businessman. I was a climber, a surfer, a kayaker, a skier, and a blacksmith.”

“Patagonia’s image arises directly from the values, outdoor pursuits, and passions of its founders and employees… Our image is a direct reflection of who we are and what we believe.”

In his younger days, Yvon slept in an old army-surplus sleeping bag 200 days a year or more. He didn’t own a tent until he was 40.

Yvon intimately knew who the customer was. The customer was himself – an adventurer.

Such self-knowledge can pay major dividends. It has been linked to greater happiness, decision-making and meaning, among other attributes.

Do you know who you are?

Look at your calendar. Look at your bank account.

Ask yourself: Where does my time go? Where does my money go?

That’ll reveal precisely who you are.

Know who you aren’t

“I would never be happy playing by the normal rules of business; I wanted to distance myself as far as possible from those patsy-faced corpses in suits I saw in airline magazine ads.”

One of Yvon’s stated goals was to prove you could break the rules of traditional business and make it not only work but work better.

Knowing what you don’t like can be as powerful as knowing what you do like.

The legendary investor Charlie Munger once said, “All I want to know is where I'm going to die, so I'll never go there.”

This is not only a saying. It’s a way of being.

Know who you aren’t, so you’ll never become it.

Simple is better

“I believe the way toward mastery of any endeavor is to work toward simplicity… From my feeble attempts at simplifying my own life I’ve learned enough to know that should we have to, or choose to, live more simply, it won’t be an impoverished life but one richer in all the ways that really matter.”

The hallmark of great entrepreneurs is their ability to simplify things: Henry Ford streamlined manufacturing, Steve Jobs made computers easier to use, Elon Musk made space travel commonplace.

Across health, finance, business, art, everything, simplicity is the path to prosperity.

Eating better leads to a healthier life.

Living within your means builds wealth.

Writing more makes you a better writer.

These ideas are boringly simple, yet their effectiveness is why they’ve been repeated for thousands of years and will continue to be.

Da Vinci is known to have said: “Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.”

On the other hand, complexity is just a way for someone else to get rich.

Shoot for 80%

“I’ve always thought of myself as an 80 percenter. I like to throw myself passionately into a sport or activity until I reach about an 80 percent proficiency level. To go beyond that requires an obsession and degree of specialization that doesn’t appeal to me. Once I reach that 80 percent level I like to go off and do something totally different.”

Consider the philosophy that “good enough” is often good enough, saving valuable resources like time, money and effort for areas where they truly count.

Perfectionism often comes with many hidden costs.

As Voltaire famously said, “Perfect is the enemy of good.”

Start now, learn later

“You can’t wait until you have all the answers before you act.”

Yvon didn’t go to business school. He just started making and selling stuff. That’s it.

The easiest place to fail is at the starting line.

The desire for uncertainty trips us up. However, as thinker and writer Shane Parrish writes in an essay, “more information often leads to worse decisions.”

Answers come through action.

Push yourself………………………but not too far

“Doing risk sports had taught me another important lesson: Never exceed your limits. You push the envelope, and you live for those moments when you’re right on the edge, but you don’t go over. You have to be true to yourself; you have to know your strengths and limitations and live within your means.”

Another Charlie Munger reference: He and Warren Buffett had a “too hard” pile for investments deemed unworthy of the effort because they fell outside of their circle of competence.

It shows how useful it can be to define your limitations — your circle of competence.

You can always push the limits but can’t always survive the consequences.

Keep yourself in “yarak” (stay hungry)

“...there were no crises except those that were invented by management to keep the company in ‘yarak,’ a falconry term meaning when your falcon is super alert, hungry, but not weak, and ready to hunt.”

In falconry, the practice of “yarak” ensures the hawk remains fit and primed for hunting.

Similarly, for us ground dwellers, achieving such an active state hinges on having a sense of purpose.

Purpose is linked to numerous benefits, including longevity, robust personal relationships, improved mental and physical health and wealth.

It’s a testament to the value of maintaining a hunger for something meaningful.

The more you know, the less you need

“The more you know, the less you need. The experienced fly fisherman with only one rod, one type of fly, and one type of line will always outfish the duffer with an entire quiver of gear and flies.”

Patagonia’s rugged self-sufficiency and frugality ethos, highlighted by their “Don’t Buy This Jacket” campaign, emphasizes repairing over purchasing.

This philosophy teaches that life’s best experiences don’t require more stuff.

We often seek comfort in material things due to self-induced fears and insecurities. Writing about ultrarunning, artist, writer and runner extraordinaire Brendan Leonard summed it up: “You pack your fears and anxieties. Put more simply, the more you worry, the more stuff you bring.”

Experience shows that reality seldom aligns with our imaginations.

Process over goals

“The Zen approach to archery or anything else, you identify the goal and then forget about it and concentrate on the process.”

Unless you’re Alex Honnold, one does not simply climb a mountain. You need to organize gear, attach a belay, secure anchors, set lines, etc.

How far you go is ultimately the result of the many individual steps you take, not where you set your sights.

As James Clear put it: “You do not rise to the level of your goals. You fall to the level of your systems.”

Curiosity is a virtue

“Uncurious people do not lead examined lives; they cannot see causes that lie deeper than the surface. They often believe in blind faith, and the most frightening thing about blind faith is that it in turn leads to an inability, even an unwillingness, to accept facts.”

Cats are actually on to something.

Instead of certain death, curiosity is like a mental black light, revealing the opportunities and pitfalls all around you.

Research has shown curiosity is associated with a wide variety of advantages, such as higher levels of creativity, positive emotions and success.

Money should be an essential thing, but not everything

“If you want to die the richest man, then stay sharp. Keep investing. Don’t spend anything. Don’t eat any capital. Don’t have a good time. Don’t get to know yourself. Don’t give anything away. Keep it all. Die as rich as you can. But you know what? I heard an expression that puts it well: There’s no pocket on that last shirt.”

Those are the words of Susie Tompkins Buell, co-founder of The North Face.

Yvon seemingly found it necessary enough to include in his book as a representation of their shared attitude toward money and the corporate lifestyle.

Although managing your finances should be a high priority, obsessing over money can lead to unethical behaviors and addictive habits similar to substance abuse.

If money isn’t for living a fulfilling life, then what’s it for?

Wealth is more than just money. Just consider people near the end of their lives also regret having worked so hard in life at the expense of living it.

Eventually there is no later for all that you’ve saved for later.

Don’t make happiness the goal

“[M]aking a profit is not the goal, because the Zen master would say profits happen ‘when you do everything else right.’”

If a business’s goal is profit, life’s goal is happiness. Similarly, happiness generally comes from not making it the goal but doing everything else right – taking care of your health, nurturing relationships, giving back, living with purpose.

Henry David Thoreau equated happiness to a butterfly, saying, “the more you chase it, the more it will evade you, but if you notice the other things around you, it will gently come and sit on your shoulder.”

Master the art of living: Pursue excellence in all you do

In the book, Yvon quotes English philosopher L.P. Jacks, a sentiment that encapsulates Yvon’s life quite well and gives us something to aspire to:

“A master in the art of living draws no sharp distinction between his work and his play; his labor and his leisure; his mind and his body; his education and his recreation.

He hardly knows which is which.

He simply pursues his vision of excellence through whatever he is doing, and leaves others to determine whether he is working or playing.

To himself, he always appears to be doing both.”

Some aspects of life are binary, like hot or cold and day or night. However, many situations embody a “both/and” nature, such as balancing work and play or managing to both spend and save.

This ability to see the complexity in life is known as non-dual thinking. L.P. Jacks’s words reveal that this approach isn’t just a different way to think but can usher in a new way of living.

Following Yvon's example, if done correctly, it becomes hard to distinguish whether you’re working or playing.