The Joy of Giving Up on “Having Enough”

Artists, athletes and the art of non-finito

Hi,

Things are going to start looking a little different around here – as this newsletter and you deserve that attention (more on why next week!). We’re going to have ourselves a proper newsletter. Thanks for sticking with me. And if there’s any feedback you’d like to share, send me a message or comment. Your thoughts matter.

In this edition:

What artists can teach us about chasing goals

Why money doesn’t create lasting contentment

Did Charlie Munger love the song, “Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald”?

What would life look like if you had enough money to never worry?

I don’t know. Because that’s impossible.

What I can show you is what life really looks like.

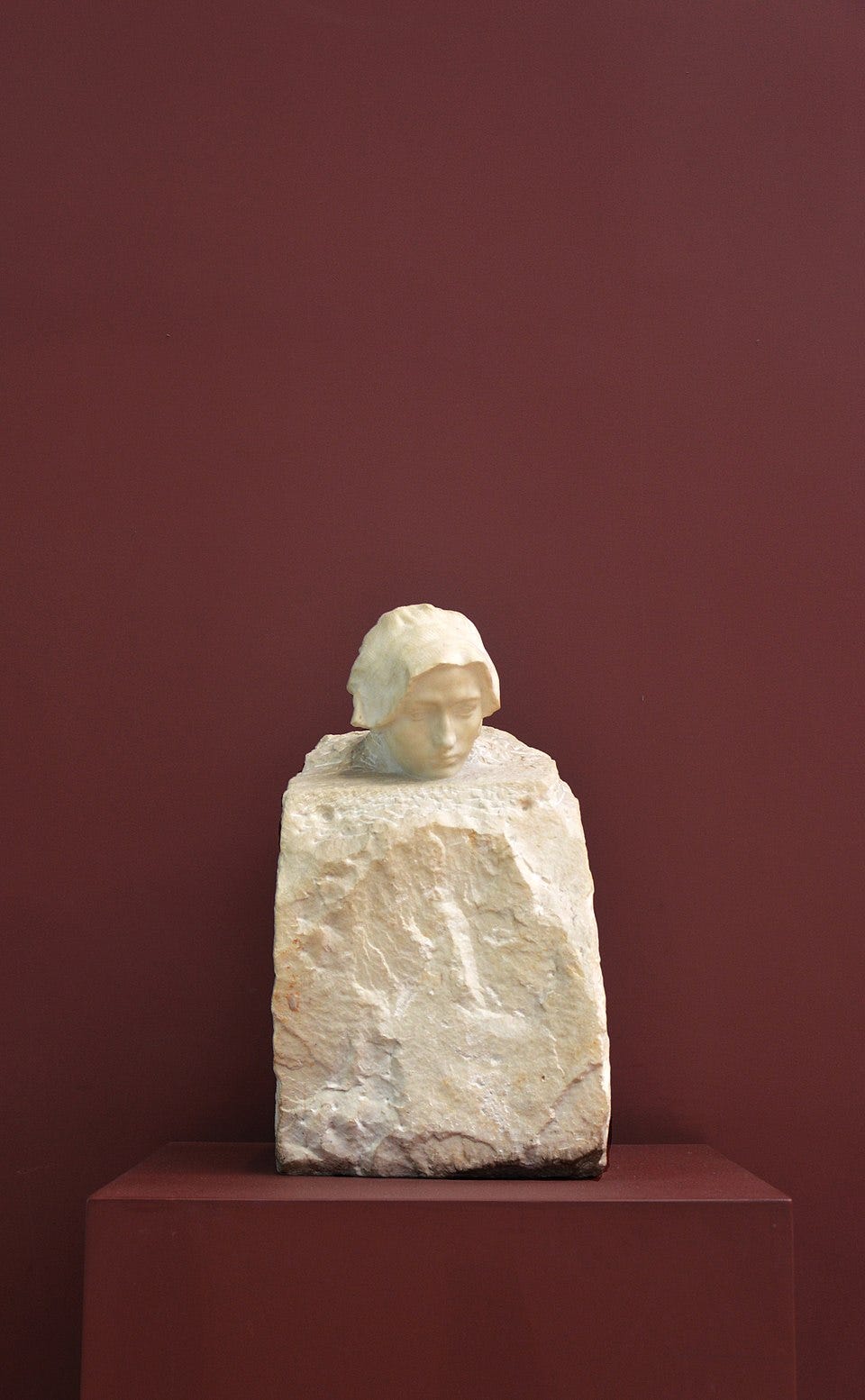

It’s formed by hammer and chisel. It’s then refined with smooth brushing and the hard press of carving tools. All of it orchestrated by chalk-dusted calloused hands, hands that then lay off what creation has begun.

Go ahead – take a look. This is your life:

An unfinished masterpiece.

The marble figure is the work of Auguste Rodin, who at times left sculptures incomplete on purpose, using the art technique known as “non finito.” Translated from Italian, it literally means “not finished.” Detailed figures seem to emerge from roughly-hewn blocks of material, as if the sculptor stepped out for a smoke break.

Rodin believed that this unfinished state made his work appear more alive, evoking a sense of vitality, movement, timelessness.

Practiced by other artists like Donatello and Michelangelo, the art of non finito is said to be inspired by a philosophical principle of Plato – that a work of art could never completely mirror its heavenly counterpart.

And so it is with life on Earth, where a polished, happily-ever-after state of being is impossible. Our happiest times in life do not last – just moments that harden into memory. Because life is still not finished, still unfolding, still being created.

As poet Robert Frost put it:

“In three words I can sum up everything I’ve learned about life: it goes on.”

The world changes, as we ourselves change – a fact poetically expressed by Heraclitus when he said:

“No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it is not the same river and he is not the same man.”

This is why I picture the bodiless, headless, dismembered shapes of Rodin and other artists whenever someone serves up the prescription to seemingly every modern affliction – greed, consumerism, workaholism, you name it:

Enough.

It goes a little something like this: the secret to a happy financial life is to “know when enough is enough.” The ultimate goal is contentment, to have enough money to meet your basic needs while keeping your expectations of life in check. You wouldn’t obsess over money, stuff or success, nor would you be an anxious, depressed a-hole, if only you knew when enough was enough.

Maybe your goal isn’t to get filthy rich. You just want enough to enjoy life and not worry.

That’s my goal, too, or rather, it was. But two things changed my mind. One was experiencing a few difficult life moments. You know the ones. Those times in life when you realize all the money in the world can’t reverse the laws of biology or physics. Maybe money can buy you happiness, but it’ll never buy miracles.

The other thing was less devastating but just as eye-opening. I wrote an article about the F.I.R.E. (financial independence, retire early) movement, and I had a chance to speak with a few people who retired by age 40. But instead of finding a sense of freedom and lasting joy, they mostly found the opposite.

One person I spoke to had been a doctor who burned out while running his own successful but overly hectic medical practice. He thought what would make him happy was building enough wealth to walk away from his work. So he saved nearly every dollar, sold his business and retired. Yet, not long into his early retirement, he felt miserable. Secure and in want of nothing, he was bored; all the time and money had no purpose. He escaped the storm of chaos only to find himself rudderless in the open sea.

Perhaps a curse of the human condition is that we weren’t meant to be content. Research suggests we are wired to strive, stubbornly attracted to novelty and exploration. What helped us traverse continents, now blocks us from finding contentment.

So I’m not quite sure what is “enough” other than a few million bucks and a lobotomy.

After all, it’s not a matter of will power, as if one can simply choose a state of contentment in which our needs and wants are locked in stone, marble or ink. I can tell you 20-something me had a vastly different outlook on life than 40-something me does today. In a way, the advice of “know when you have enough” sometimes feels like the financial equivalent of telling a depressed person to just “be happy.”

We can see this in some highly successful people – those who are extremely rich or who have achieved great feats of business or sport or whatever, yet remain unhappy.

Often in life we’re pressured to be somewhere: to become a degree-holder, to land a high-paying job, to own a home, to become a millionaire. We need to be somewhere in life to win, to be happy, to be content.

But what if there is no “there”?

Instead, what if joy and actual contentment is found in the art of non-finito, not trying to reach some ideal finish. Maybe the work of Rodin and other artists offers a different path to creating a happy life – one on which you purposefully don’t finish, you aspire to go on past the finish line, as life goes on.

Because what’s the point of “enough,” anyway?

I’m not an artist. I don’t paint pictures, sculpt busts, write songs or pen poems. But I fish. And fishing is an example of the art of non-finito.

There are days when you catch one after the other, as if they’re dying to get out of the water. Some days you catch the big one, so big that it makes you stop and watch it wade in your bucket like at an aquarium. Other days you catch little more than a sunburn. And other days, if you’re fishing with young kids like I have the past several years, you’re just hooking worms, tying knots and untangling lines.

There’s no winning or losing in fishing. Unlike a traditional sport, fishing is open-ended. There isn’t a type, size or quantity of fish that signifies you’ve finished fishing. If you enjoy doing it, the game continues. Any true angler would choose to fish tomorrow rather than catch the biggest fish of their life today and then have to quit.

Few achievements satisfy in truth. The possible exceptions being getting married, having kids and folding a fitted sheet.

Earlier this year, the pro golfer Scottie Scheffler went viral for his philosophical meditation on success, asking “What’s the point?” About winning at golf, something he’s worked tirelessly for his whole life, Scheffler said:

“It’s fulfilling from a sense of accomplishment, but it’s not fulfilling from a sense of the deepest places of your heart. There’s a lot of people that make it to what they thought was going to fulfill them in life. And then you get there, then all of a sudden you get to No. 1 in the world, and they’re, like, what’s the point?”

Scheffler’s epiphany is common among elite athletes. Perhaps, no more so than by Olympians, who train religiously for most of their young lives for what is often only one shot at gold. And for a brief time, they are the center of the world’s attention.

Then, poof! It’s over. Like fireworks in the sky, the bright imprint of athletic performance fades and the crowd changes the channel.

Life goes on.

Megan Neyer made the 1980 Olympics, only to find her dreams dashed as the U.S. boycotted the games in Moscow. When athletes similarly learned the games in 2020 were cancelled, Neyer wrote an open letter to the U.S. team:

“You may think that making that team or winning that medal would “make your life.” I promise you, it won’t. It is one life experience, and you write the story about it based on what you make of it. You’ll reconnect with your dream, or you’ll set your sights on new ones, and proceed from there.”

Neyer was telling them they are not defined by accomplishments. Even being an Olympian won’t fill one person’s life story.

Several experts, like David Epstein, rightly pointed to Scheffler’s comments as an example of what psychologists call the “arrival fallacy”:

“[T]he mistaken belief that finally “arriving” at a long‑sought goal will deliver lasting happiness. In fact, “arrivals” sometimes recalibrate the happiness bar and send us chasing the next ever-greater milestone, a cycle researchers call hedonic adaptation… perhaps we simply expect too much of our own victories.”

The writer Anne Lamott simply put it:

“If you’re not enough before the gold medal, you won’t be enough with it.”

We can draw parallels to money. If you’re not enough before you have a lot of money, you won’t be enough with it.

Yet, it feels like the point of all this financial stuff is to – if not get rich – cross some sort of finish line, achieve a goal. Maybe it’s to be debt free or earn more. Or maybe it’s to travel the world, buy a home, retire. Once you achieve that goal, you’ll feel better, happier, less stressed, in control – finally content.

But plenty of life examples prove the fallacy of fulfillment from money. The Getty family had wealth beyond imagination and yet suffered numerous tabloid tragedies: affairs, kidnappings with severed ears, heroin overdoses.

It seems the emptier a person’s heart is, the more he or she feels the need to buy, own and consume. Since we don’t feel fulfilled, it feels like we’re “not there yet,” so we keep pursuing that goal in the distance. Some people grow rich and find their only identity is to show how rich they are – buying a little nicer stuff.

The alpinist Mark Twight warned:

“Don’t be a fool who builds a monument to his achievements and turns to stone along with it.”

The pursuit of some goal under the belief that it will lead to some kind of happy state for the rest of your life is likely to do the opposite. In the classic Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, Robert Pirsig had some harsh words about goal-oriented thinking, writing:

“To live only for some future goal is shallow. It’s the sides of the mountain which sustain life, not the top. Here’s where things grow.”

Having enough or being content by definition are objectives, goals, things to achieve. And like any goal, they ultimately won’t provide lasting fulfillment. But I’d argue they’re not even attainable, like an insurmountable climb, a mountaintop always looming in the distance no matter how hard you trek.

Because life is not finished. Life goes on. We can only control so much. There is not enough to keep us from ever making a wish or having to say goodbye.

There’s not enough to quiet every desire, as if you even want that. Research indicates that having something positive to look forward to can boost happiness and reduce stress.

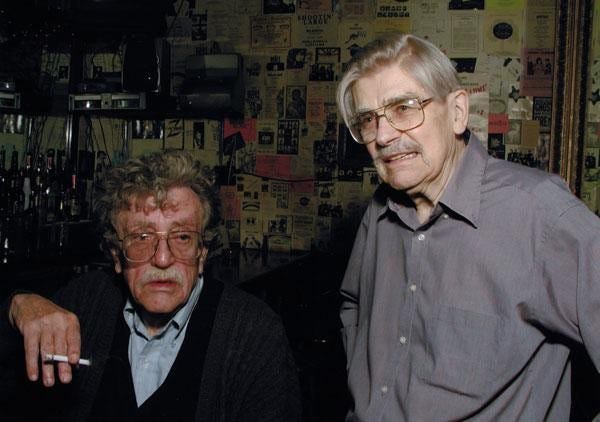

There’s a story often shared on blogs and social media featuring the writers Kurt Vonnegut and Joseph Heller. At some lavish party, Kurt Vonnegut asked Joseph Heller, “How does it feel that our host may have earned more yesterday than Catch-22 has in its whole history?” Heller replied calmly: “I’ve got something he can never have … the knowledge that I’ve got enough.”

But that’s not the end of the story. There’s an important fact that’s always left out: after this interaction, both men kept writing. They kept publishing books. They both kept trying to write their best book yet. Not for more fame, or money, or awards, but for the joy of writing, the thrill of forming that next killer sentence, the magic of giving life to a story born out of thin air.

All in all, life finds a way to laugh at any thought of contentment.

While it’s important to plan for the future – one in which you are not in desperate need of money or seeking external affirmation – it’s also important to understand that there is no perfect calibration.

There’s no heavenly destination, no point at which everything unwanted goes away because you’ve made it and now get to spend the rest of your life in that moment of being there. There are no “rest-of-my-life” solutions.

The good things in life are often ineffable, a place that is no place at all. Life is a series of moments. And the key to fulfillment seems to be learning how to enjoy them as they happen.

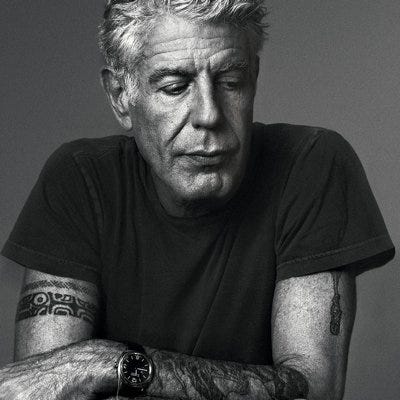

Anthony Bourdain, known for many televised great moments, said:

“To sit alone or with a few friends, half-drunk under a full moon, you just understand how lucky you are; it’s a story you can’t tell. It’s a story you almost by definition can’t share. I’ve learned in real time to look at those things and realize: I just had a really good moment.”

Noticing the good moments of life unfolding – maybe that’s the point.

As we all dance to the finish line…

If we don’t have something to move us along in life, to the good moments, it all becomes aimless – no matter how high the highs.

Mark Manson, author of The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck, sold more books than many of the most famous authors of all time. But did it translate to the life he wanted?

In a post, he wrote:

“You’d think selling 20 million books makes you satisfied with life. It doesn’t…

[H]ere’s what nobody tells you about achieving your dream: the next morning, you wake up without a dream.

Instead of turning on my laptop and working toward a goal that day, I turned on my Nintendo and played Zelda for six hours.

After a few days of that, I remember thinking:

‘What’s the point of all this? You worked for 10 years just to play Zelda all day?’

Take it from someone who got everything he thought he wanted:

It’s the wanting of the dream that is satisfying, not the having.

It’s great to achieve your dreams, but make sure you’ve diversified your dreams enough, across enough areas of your life, so that you never wake up one day without one.”

Artists are creatures of habit, rising to work on something that never ends.

Ernest Hemingway, a man who when he wasn’t drinking or hunting (or both) set strict hours and daily word quotas, wrote:

“We are all apprentices in a craft where no one ever becomes a master.”

What’s more, in this failing pursuit, artists find joy, as if a smiling Sisyphus. The pleasure is in work never finished.

Walt Whitman never stopped working on his one major work, Leaves of Grass, publishing seven different editions over his life.

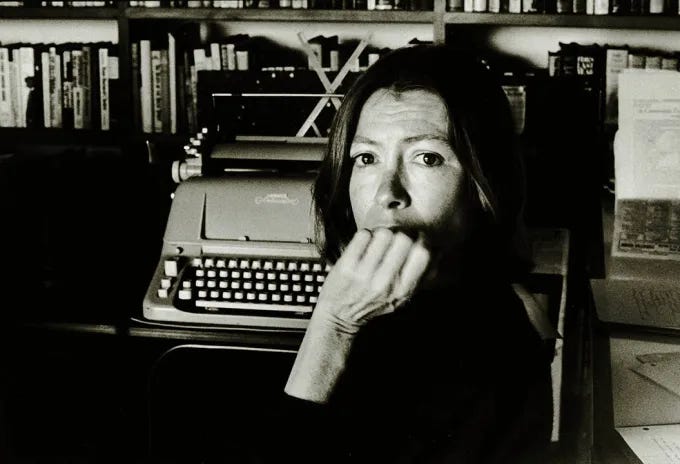

Joan Didion was known to still make edits to published copies of her books.

The point? Simple, even childlike. They enjoyed doing it.

The late director David Lynch summed it up well:

“I’m just, you know, kind of happy in the doing of things… Working on a painting or working on a piece of sculpture. Working on a film. One thing I noticed is that many of us, we do what we call work for a goal. For a result. And in the doing, it’s not that much happiness. And yet that’s our life going by. If you’re transcending every day, building up that happiness, it eventually comes to: it doesn’t matter what your work is. You just get happy in the work… If the result isn’t what you dreamed of, it doesn’t kill you, if you enjoyed the doing of it. It’s important that we enjoy the doing of our life.”

That’s the art of non-finito. Artists have liberated themselves from the belief of arriving anywhere, indulging in the joy of the journeying.

It’s not a realization reserved for artists or athletes, as the Nobel scientist Richard Feynman shared the value of doing over being:

“Fall in love with an activity and do it! Nobody ever knows what life is all about and it doesn’t matter. Nearly everything is interesting if you get into it. Work as hard as you want to on the things you like to do best. Don’t think about what you want to be, but what you want to do.”

I’ve always assumed the point of building wealth - if not simply being financially comfortable - was to reach a life situation that once attained would remain unchanged for the rest of my days. But this pursuit, like many achievements, puts pressure and stress on you and actually makes it harder to attain because you’re always second-guessing yourself: am I on the right path? Have I reached my destination? Preventing yourself from settling into the thing that gives you joy, meaning, purpose.

Those who seem to have found joy in a pursuit often say the goal of life is an action — a verb (doing) — not a noun (enough), some kind of hopeful way of being.

For the investor and thinker Charlie Munger:

“I think that a life properly lived is just learn, learn, learn all the time.”

I have to wonder if his favorite song then was “Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.” As investigators and historians discovered more details about the tragic sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald, songwriter Gordon Lightfoot would learn about them and update the lyrics so that it would sing true.

While he may not have been speaking in philosophical meditations, Munger’s sidekick, Warren Buffett, expressed how people often win when they aren’t focused on the result:

“The people that win are the ones with eyes on the field and not the scoreboard.”

It seems to me that those who really appear to be content or have found lasting joy in life are those who are doing something, not striving to be a particular condition or reach some label.

A rich life is a creative life — and creativity is an action. The way to joyful contentment in life isn’t by having or being something. Rather, it’s by doing something.

The late actor Robert Redford echoed the sentiment of Pirsig in finding joy around you, not in the distance:

“To climb up the mountain is the fun, not standing at the top. There’s nowhere to go. But climbing up, that struggle, that to me is where the fun is… But once that’s over, that’s kind of it… I don’t look too much beyond that.”

Some might call this a “process over goals” or “journey-is-the-destination” mindset. But I think it’s deeper than that. Process implies a system to achieve a particular result. With craft, what you produce is not the main thing.

This insight – turning your attention to a craft – doesn’t mean giving up on building wealth, living a minimalist life or to stop caring about money.

I’d argue it’s the opposite: it makes it easier to create a strong financial foundation because you’re not distracted by unnecessary pursuits that disrupt the support of your craft – whatever that source of joy is: art, taking care of family, leading a company, being the friend that makes the plans.

The key to happiness or contentment is learning your craft that generates all those moments that make up a life. Which means the key to personal finance is figuring out how to use your money to create the environment for those enjoyable moments.

We’re all striving for something. If there’s something that inspires you or has meaning for you, and you want to be connected to it, find the version of it that works for you. And then practice being good at it day after day – non-finito.

Maybe in the process you get rich, maybe you don’t. Maybe you need more money, maybe you can get by with less.

Either way, we keep cutting into marble, scribbling into books, adding a new verse, casting into lakes or seas, swinging for the fairway.

Maybe there needs to be another phrase, better than “having enough” or “being content.” One that reflects the unfinished nature and more accurate depiction of life. Perhaps, we should all be seeking the virtue of “living well.”

As Rodin said:

“The main thing is to be moved, to love, to hope, to tremble, to live.”

And when you are living, obviously, life is not finished. Not, at least, until you die. As the Trappist monk Thomas Merton wrote:

“We are invited to forget ourselves on purpose, cast our awful solemnity to the winds and join in the general dance.”

What’s the point?

“The meaning and purpose of dancing is the dance.” (Alan Watts)

And the dance doesn’t end until the music stops.

Notes to my future self:

Life is non-finito; joy is in the doing.

“Enough” can be a mirage (arrival fallacy).

Build a craft; use money to support moments. “A rich life is a creative life, and creativity is an action.”

Until next time (now sooner rather than later),

J.S.

Jacob, this is a masterpiece. I upgraded to Paid subscriber, I should have done it earlier, my bad. I will share it in my blog this Friday as well. And so relevant to me as I am contemplating retirement and, you know, I still enjoy my craft :-)

Sharing this with everyone I know. What a fantastic read!