The Financial Risks of the Stories We Love

How stories can change the way we think, act and use money

When we make a financial decision, we compare stories. As Nobel Prize winning economist Daniel Kahneman said, “No one ever made a decision because of a number. They need a story.” Some stories, however, are more effective than others – and there can be significant financial risks to the stories we love most.

Also in this issue: a Q&A with the writer behind one of the most creative financial blogs out there, indeedably.

Please subscribe, if you haven’t. Right now, IT’S FREE! Where else are you going to find a deal like that in this economy?

If you’d like to help support The Root of All and yourself by sponsoring a post, the email line is open: rootofall@substack.com

If you ever wondered why we make certain financial decisions (should I buy the Sketchers or Gucci shoes?)… or if you are wondering now what the hell were people thinking when they plowed their entire life savings into digital pictures of primates or canine-themed money…

Well, here’s a story:

Once upon a time, a young man was going to revolutionize the world.

He was a recent college graduate heading out into the real world with an irrational sense of optimism, but without a job. Then one day, he found a job posting for “brilliant, ambitious candidates” to help “market-leading” companies run a major tech company’s “most innovative software ever” – and by doing that, they would “revolutionize the world.” Visions of the future danced in his head: he would learn valuable skills; he would earn lots of money to buy lots of nice things; and people would know him as being at the forefront of a technological revolution.

He applied, and as luck would have it, he was offered the position.

But there was a catch. He was required to undergo training in Boston, which he would have to pay for himself, including any travel and lodging. That would require him to drain his savings and say goodbye to his girlfriend. And then once his training was over, he would technically work as a contractor with no guarantee of any work at all.

Suddenly, the illusion disappeared. What seemed like a life-changing job opportunity was revealed to be an attempt to take advantage of hungry, impressionable college grads for outsourced work. So much for revolutionizing the world. The young man naively fell for a story that activated his earnest desires and emotions.

I can’t blame him. After all, that young man was me.

Sure, I don’t know if this “job” was a total scam. The other young idealistic candidates who did take the offer may be sailing around Cape Cod in their yachts right now eating fresh caviar while admiring gold-plated plaques thanking them for their service in revolutionizing the world.

What I do know is the reason why I didn’t initially suspect the job posting as too good to be true. I had become captivated by a “hero’s journey” story. I heard the call to adventure and the promise of a reward. If you don’t know it, you do. This is a common story structure shared among cultures worldwide. It’s found in ancient myths and fairy tales, many Hollywood movies (think Star Wars), TED talks, political slogans and ads for cheese crackers.

Why are there seemingly common narratives around the world? Because that’s what we’re designed to do. As social beings, stories are our way to exchange information, promote values and build relationships with each other. They are how we build trust in strangers. Interesting and emotionally engaging stories stimulate our brains in a way numbers can’t, which is why we remember stories much better than data.

Stories can explain why we buy one brand of shoes over another, why we save money in a bank or under the mattress, why we choose to invest in a boring low-cost index fund or put it all, including little Johnny’s college savings, in Bitcoin.

The power of stories has been recognized since antiquity, as Plato supposedly said,

“Those who tell stories rule society.”

But there are two modern developments that I think make it urgent to understand the role stories play in our financial lives:

1. The information age is in hyperdrive.

Research from Loup Ventures estimates around 70-80% of our waking hours are spent consuming information. (We could say the other 30% is spent eating, commuting and using the bathroom, but we all know what we do when we’re at the dinner table, behind the wheel or on the toilet.)

Source: Carat, Loup Ventures

Part of that information binge is exposure to an estimated 4,000 to 10,000 ads per day. These are all stories working to gather a portion of our limited attention, time, energy – and money.

2. There are more things to do with our money than ever before.

You can buy anything on Amazon. You can place bets on any game right from your phone. You can invest in digital coins, paintings by Picasso, even rare historical artifacts like an original copy of the U.S. Constitution. You can pay with cash, debit, credit, Venmo, PayPal, buy now/pay later.

Together, it is easier than ever to become financially carried away by stories.

Case in point: reports of young consumers racking up large amounts of debt using buy now, pay later services after watching videos of their favorite social media influencers pitching sponsored products.

The same can be said of the recent crash in stocks and cryptocurrencies as people realize stories like “stocks only go up” and anything other than NASA goes “to the moon” are just fantasies.

It’s a good time then to look at the financial risks of the stories we love.

Slaughterhouse-Stonks, or so it goes

Here’s another story about a young man.

One day, a college student decided to invest in the stock market for the first time. He learned about a group of traders sharing tips online and making lots of money. They even used their own irreverent lingo, calling stocks “stonks” and investment gains “nuggies.” What’s more, they were turning Wall Street on its head. Their strategies were leveling the playing field for the average investor and punishing the Wall Street elite who bet against them.

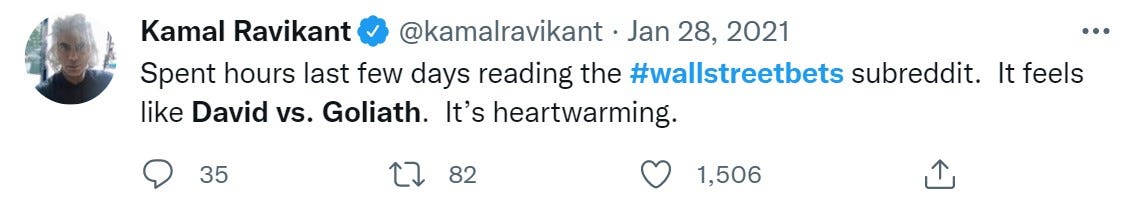

People on social media are calling it an inspirational David vs. Goliath story.

Suddenly, people all over social media were posting about how easy and profitable it was to trade stocks. The young man was attracted to the idea of joining the frontline of this revolution, and earning a few extra dollars to help pay the rent. So he followed their lead and bought some stocks. Sure, he didn’t have a good reason for investing in a beleaguered video game store and struggling theater chain. But who cares, he thought, stocks only go up.

Except they didn’t. At least, not for him. His shares rose a little, then crashed. Soon he was losing money he couldn’t afford to lose. The rent was due. So, he sold his shares. In the end, he had gotten burned, telling the New York Times: “I just got caught up in the social media hype and just dove right into it. I fell for it.”

Of course, this is a story about the Wallstreetbets saga, and our young protagonist here wasn’t the only one to get caught up on the hype. Neither was the collective hype limited to GameStop and AMC shares, as it helped launch the prices of “story” stocks, NFTs and, most notably, cryptocurrency. In one CNBC survey of people who traded cryptocurrencies, the top reasons given included “it was exciting,” “it feels like a game” and “social media personalities encourage investing.”

So far, 2022 has been a different story. For various reasons, the most talked-about investments over the past couple years, from Tesla to Bitcoin, have suffered heavy losses. With the billions in value that have gone up in smoke so have the stories that propelled them. As Josh Brown remarked, these stories of the past year have been proven to be more fiction than fact: “boundless growth, total addressable market, venture-backed, innovative, groundbreaking, web3, transformational, disruptive”.

It is a classic boom-and-bust story. As asset prices rise higher and higher, exuberance takes hold and more and more people jump on the hype train until it runs out of track atop a cliff and comes crashing down.

“So it goes,” as the fatalistic aliens say in the Kurt Vonnegut novel, Slaughterhouse-Five. It has happened plenty of times before and will happen again.

While it would be easy to dunk on people who fell for the hype, it’d be better to sympathize and learn from them because we are all attracted to these types of narratives.

Vonnegut gave a famous lecture detailing the shape of stories, which can be plotted into simple graphs that rise and fall between good and ill fortune over time.

He ultimately identified six primary types of stories. Computer science professor Peter Dodds analyzed 20,000 books and found around 90-95% followed the shapes identified by Vonnegut.

This suggests certain stories may be inherently appealing, such as Cinderella, “rags to riches,” David vs. Goliath and so on. And they’re the same ones that can influence our financial decisions. Just consider the widely panned cryptocurrency commercial featuring Matt Damon. He doesn’t talk about what cryptocurrency is or what it does or how it performs as an investment. Instead, he tells a story about explorers and innovators in the shape of the “hero’s journey,” stating non-ironically “fortune favors the brave”.

There’s a reason for that – we recognize and respond to that story. If stories then are like dog whistles, it helps to understand how they can change our emotions and money-related behaviors.

How the shape of stories shape us

It essentially comes down to a potent mix of chemistry and psychology.

Research from psychologist Paul Zak shows that emotionally engaging stories can induce the release of the hormone oxytocin in our brain and make us more empathetic. This mechanism essentially helps us form relationships and make judgements about the world around us.

In one experiment, Zak and a team of researchers had people watch an emotional video about a grandfather spending the last bit of time with his young grandson who was dying from cancer. After watching the video, these individuals had higher levels of oxytocin in their bodies and nearly all of them donated a portion of what they were paid to participate in the experiment.

When the storyline of the video was adjusted and made less personal, without any information about cancer or what this old man and boy were doing together, the participants were far less aroused and less likely to donate their money.

Basically, oxytocin makes us more sensitive to social cues around us, which motivates us to help others. Essentially, well-structured stories can change our brains and affect our behavior.

It explains why people were inspired by Elizabeth Holmes when she told the personal story of her uncle dying from cancer to promote Theranos.

But there’s a twist to this story.

Stories are like a two-way street. They reach out to us, and we reach out to them.

As writer Maria Konnikova writes in her book, The Confidence Game, when it comes to the mental wall between us and a con artist, “We’re quite good at getting over that hurdle ourselves.”

The desire for stories, the desire for an explanation, the quickest explanation we can muster, makes us vulnerable to fraud and scams.

Konnikova writes:

[O]ur minds are built for stories. We crave them, and, when there aren’t ready ones available, we create them. Stories about our origins. Our purpose. The reasons the world is the way it is. Human beings don’t like to exist in a state of uncertainty or ambiguity. When something doesn’t make sense, we want to supply the missing link. When we don’t understand what or why or how something happened, we want to find the explanation. A confidence artist is only too happy to comply—and the well-crafted narrative is his absolute forte.”

Stories written for your money

Perhaps, no other group of people on the planet knows the effectiveness of stories better than the advertising industry.

Having worked in advertising, I know the little secret to a successful ad isn’t to sell a product but an entire world view. After all, buying stuff is often not about the stuff but about identity. It’s not surprising then that one survey found that half of US consumers said they want the brands they use to feel like a best friend.

Advertising tries to connect us to the identity we desire. As ad legend David Ogilvy put it:

“It isn’t the whiskey they choose, it’s the image.”

A good example of how a story can change our perceptions to match a desired identity comes from the TV show “Nathan for You.” Here, Nathan uses a story to convince a focus group of children to want a toy they had originally dismissed:

My personal favorite real-world example of engaging commercial storytelling is the MasterCard “Priceless” ad campaign. It’s not about a low APR or zero transfer fees. It’s about people using their credit cards to buy things to create memorable experiences. It’s an emotional narrative about how life is short, and you don’t want to be the person who misses the opportunity to create moments that you’ll remember on your deathbed and your children will remember on theirs, no matter the cost. It’s basically what Vonnegut called a “man in hole” story, encouraging us to overcome the doldrums of everyday life by making it exciting again.

Ultimately, stories have the ability to quiet our voice of reason. At best, falling for an emotionally engaging story could lead to some overspending; at worst, it could lead to something much more sinister. Professor Nicholas O’Shaughnessy wrote in his book, Selling Hitler: Propaganda and the Nazi Brand, that a “core part of Nazi grand theory was the dethronement of reason and the celebration of emotion… and therefore the nature of its propaganda appeal was also to feeling rather than thinking.”

I’m not saying credit card companies are Nazis, but they speak the same language.

Which brings us back to the quote I used at the top from economist Daniel Kahneman:

“No one ever made a decision because of a number. They need a story.”

Since we need stories to live, to paraphrase Joan Didion, how can we navigate them – and their financial risks – responsibly?

Sidestepping the risks of good stories

Trying to avoid stories because of the risk some might work against you is like trying to avoid eating because of the risk you might choke. That doesn’t mean we’re powerless. Here are a few ways I think that can help us think sensibly about stories, especially those that impact our finances.

1. Accept that you are not immune

What do the likes of Bernie Maddoff, Elizabeth Holmes and Adam Neumann have in common? Not that they duped a lot of people with stories, but they duped a lot of rich, successful, powerful, brilliant, put any sensational adjective here, people. These people put their money and reputations on the line for a story. Take former secretary of state George Shultz who labeled Holmes as “the next Steve Jobs or Bill Gates.”

It doesn’t matter whether you’re young or old, a genius or billionaire, we can all be a little foolish with money when it comes to a good story. For example, contrary to our ageist stereotypes, the Better Business Bureau’s report has shown that younger adults lose money to swindlers much more often than the older people.

The first step then is to exercise a little humility. This can keep you from the arrogant belief that if you like a story, then it must be true.

2. Think like a scientist

As scientists constantly test and challenge their views, maybe we should constantly test and challenge our beliefs.

Organizational researcher Adam Grant said that by thinking like a scientist, “you favor humility over pride and curiosity over conviction.” It involves keeping ideas from becoming your identity, searching for reasons why you might be wrong and seeking people who can challenge your views. These are all steps that could help objectively deconstruct the stories we encounter.

Think your Uber driver is on to something with his “hot stock” tip? Think of all the reasons that story could be wrong, namely that he is still driving you around for money. Now, run it by your friend who is a financial adviser and who may have a different take on this guaranteed winner.

3. Or, think like a literary professor

The author George Saunders wrote:

“[T]he part of the mind that reads a story is also the part that reads the world; it can deceive us, but it can also be trained to accuracy; it can fall into disuse and make us more susceptible to lazy, violent, materialistic forces, but it can also be urged back to life, transforming us into more active, curious, alert readers of reality.”

As a creative writing professor, Saunders teaches students that to become a better writer, you must become a better reader. His four-step process for critiquing a story is to “read, have a reaction, notice it, and articulate it.”

In other words, you train yourself to pay close attention to how a story makes you feel and then investigate why you feel that way. This can reveal a story’s true meaning and its effect on you. When making a financial decision, for instance, write down what you feel about each choice and why. Often, the truth needs a little coaxing.

Becoming better readers can help us read between the lies, even those we tell ourselves. Maybe we shouldn’t think of this as a trick, but rather a responsibility. Just consider the numerous posts online from from people discussing suicide after losing money in the recent cryptocurrency crash.

It’s important to take the responsibility of language seriously. We should probably heed the words of the poet and theologian Eugene Peterson:

“We cannot be too careful about the words we use; we start out using them, and they end up using us.”

Coda

From a purely logical perspective, our reliance on stories to interact with the world may seem crude and inefficient. Stories can make life unnecessarily messy, leaving us vulnerable to costly mistakes.

But they also make us unique. They provide meaning and purpose to our relationships, our communities, our careers, our lives, and yes, our money. After all, money itself is just a story.

Stories allow us to change, to create the impossible, to do more than you could ever think possible, to become greater selves. Whether true or not, only a story can convince someone they can revolutionize the world.

Grab Bag

Links to various things I enjoyed recently.

A 63-Year-Old Runner Changed the Way I Think About Regret

“It’s a waste of time to think about days gone by,” she said. “What’s important is the here and now, and the future. How can you improve yourself in the days to come?”

An enlightening Q&A between Tadas Viskanta and Nick Maggiulli

I think many of the rules/guidelines in personal finance are hunches or based on intuition. However, our intuition can fail us at times. This is why I can confidently say things like “you probably shouldn’t max out your 401(k)” or “save half of your raises.” I’m not guessing, I’ve run the numbers.

Kevin Kelly’s 103 bits of advice

The one I most relate to: The biggest lie we tell ourselves is “I don’t need to write this down because I will remember it.”

Also in lists, Morgan Housel’s “few” beliefs

The one I most relate to: The luckier you are the nicer you should be.

On the Write Side of Money

A short Q&A with notable finance/business writers about writing.

In this edition, I had the privilege of interviewing the creator of one of the most interesting financial blogs out there: in●deed●a●bly. Every post is not only insightful and thoughtful but well-crafted. It’s a joy to see someone who really cares about the writing part of financial writing. So, be sure to check it out!

Describe your ideal writing experience (ex. when, where, what, how).

Ideal writing experience. There is a novel concept! If I waited for the ideal, I’d be waiting forever. I write in those stolen moments between real-life activities. Whenever a random thought, passing comment, or overheard snippet of conversation sparks the idea for a story. I’ll tap out some words at the kitchen table to see where the tale takes me. Sometimes the words flow, resulting in a post on indeedably. Often times they don’t, at which point I’ll go do something else. I learned long ago there is no point in trying to force the writing, it is supposed to be fun not a chore.

Ideal writing experience for me means no self-imposed pressure. No set publishing cadence. No deadlines. No writing for algorithms or sales targets. No baiting the panic monster. Just enjoyment.

What led you to start writing?

Writing is a device I use to work through topical questions or issues in a structured manner.

What do I think about it? How do I feel about it? Why do I feel that way?

Often, the topics I write about are things I’m confronting in real life. This tends to result in some random themes, but by the end of each story I usually better understand why I think the way I do. Sometimes, researching or writing a story will challenge my beliefs, leading me to do the thinking. Occasionally, I’ll change my mind as a result. Homeownership. Active share dealing. The marketable value of time. That financial independence was never about money, but control of time.

What trait is most important to become a good writer?

I’m not qualified to opine about how to become a good writer, any more than I am qualified to write about how to get rich or retire early. Instead, I will share some thoughts on good writing.

Good writing is about storytelling. Painting pictures with words. Expressing thoughts and ideas in a way that captures the audience’s imagination and leaves them wanting to know how the story ends.

How do you judge if a piece of writing is successful?

What is successful? Having a story go viral? Generating controversy? Sparking a debate? Starting a conversation? Receiving comments from generous readers, who invest their precious time to share thoughts, feelings, and personal experiences in response to the writing? Or is it how the author feels about the writing once the piece is complete?

I’ll be honest, success remains a mystery to me. Some of the stories I enjoyed writing the most were published to the sound of crickets. Others, that I wasn’t that happy with, became the most popular.

Who are your favorite writers?

I loved the imagination of Peter F Hamilton and the rich characters of George R.R. Martin. I enjoyed being challenged by Ayn Rand and entertained by Douglas Adams. Stephen King, J.K. Rowling, and J.R.R. Tolkien all created rich worlds that captured my imagination. Ross Gittins, Morgan Housel, and Robert Kiyosaki were great at bringing to life the behavioural psychology that drives so much of our economic and personal finance thinking.

What writing book, article or blog has helped improve your writing?

Regularly writing at indeedably over the last few years has probably done the most for improving my writing. As with any skill, practice and repetition improve performance. When I encounter a writer with a gift for telling a tale, after enjoying their stories I will ask myself why the piece worked? How was it structured? What devices did the author use to develop the characters or the narrative? Sometimes I learn a few things that I incorporate into my own writing.

The name of my site originated to poke fun at the only book about the art of writing that I have read, Stephen King’s “On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft”. He really hated adverbs!

What money book, blog or podcast do you recommend most?

Personal Finance is a journey, involving a handful of concepts, each of which is simple to master. However, being personal, we only start to hear the message about each concept at a point in our journey when we are ready to listen.

Some of the memorable writings on my journey included:

The Richest Man in Babylon – pay yourself first.

The Barefoot Investor – live within your means, automate the journey, and enjoy the ride.

Jack Bogle – don’t try to pick winners, win by picking everything while keeping costs low.

Mr Money Mustache – the higher your saving rate, the sooner work becomes optional.

Rich Dad, Poor Dad – investments generate free cash flows. Everything else is a liability.

What are your favorite sources for news, research, data, etc.?

I’m a bit of a data geek at heart, and have been known to commit the occasional crime against charts. I can often be found playing with numbers sourced from places like central banks, land registries, statistical agencies, and amazing aggregators such as OurWorldInData or PortfolioCharts.

You’re organizing a dinner party. Which three people, dead or alive, do you invite?

Three people, from the entirety of human history. For a dinner party. With me. Interesting.

I’d invite Santoshi Nakamoto, because then I’d know the answer to one of the great meme culture mysteries of our time. Plus they could tell some fascinating insider tales about Ponzi scams! Next, I’d invite the author Peter F Hamilton. His futurist imaginings are up there with Gene Roddenberry and Jules Verne. If Elon Musk can play the long game by selling batteries and electric cars to fund a Martian bus route within his lifetime, it would be fascinating to explore what other transformative changes might lie on the horizon. Finally, I’d invite Romy Gill. She cooked up one of the most memorable meals I’ve eaten, during a guest chef residency. Engaging and entertaining, the dinner party would be a success with her safe hands in charge of the food.

What is your favorite piece of advice (writing, life, finance or business)?

I could cite some fortune cookie wisdom attributed to the Stoics, Sun Tzu, or Yoda. Instead, I’ll finish with some wise words from my father: never piss on an electric fence. Turns out he was right, learning by doing is not always the best approach!

Take a Penny, Leave a Penny

A new idea, exercise, principle or tip I’ve been thinking about lately.

Failure is one of those things we like to speak confidently about until we actually experience it. I think most people in the depths of failure don’t feel grateful for the lesson they just learned. We all need a grace period. This past month I attempted to run a 100k, which I trained for all winter. It was meant to be another milestone in my running life. I only made it halfway. I failed, and still feel disappointed. But I also feel hope. Because if I still feel disappointment at this point, it means I’m chasing the right goal.

With that, I take solace in the words of Olympian Alexi Pappas:

“Imagine that all of a sudden, pursuing your goal is not an option at all for you anymore. It has been magically taken away. How do you feel? If you feel relief, then you know it wasn't right for you. But if you feel heartbroken imagining a world where you can't chase your goal, then the decision to commit is clear.”

Leave a comment if you have thoughts about this or any other topic.

Your Moment of Grace

“I’m very aware of aging and of knowing that as one ages, one is approaching death… That drive in a young person to write and publish — that’s just not there anymore. Even the thought that “I have to express myself” — it’s just not there. In the past, I’d choose to write. I wouldn’t be with my son often enough, or if my friends were going out, then I’d stay home. If there was a party going on at home, I’d go to the other room to write. It’s very different now. I’ll drop my work to be with a friend. I’ll pick up the phone. Now I think, “I’ll live.” [I]t’s different when you’re older. I don’t want to die before I can show my love to my friends and family.”

-Maxine Hong Kingston, Letters to an Artist