Stories That Make You Rich or Go Broke

Why do you make certain decisions? How can you make better ones? Perhaps, you need a better story.

I think finance is synonymous with storytelling. Wall Street publishes more stories than the publishing industry.

Exhibit A is the GameStop saga, where a group of day traders bid up the beleaguered video game retailer’s stock price high enough to cause mayhem for short-selling hedge funds. For a brief time, it was a bigger story than the global pandemic and new American president.

The significance of it all will be debated for years. What is undeniable though is its example of how stories can shape us – for better or for worse.

GameStop was a classic David-and-Goliath story featuring a merry band of retail investors taking down the big, evil elite on Wall Street. Or, it was a story about equality and dismantling a rigged system. Or, maybe it was actually a tale of smart professionals seizing a golden opportunity. Or, maybe it was story of intrigue and conspiracy. Or, maybe it was a clash of titans, billionaire versus billionaire.

The story of GameStop will be known as the genesis of a major paradigm shift, ushering in a new era for the stock market. Or, it will be a stupid, non-event.

Then there are the stories within the story, like a 10-year-old whose GameStop share returned 5,000%.

Don’t forget the Reddit group responsible, r/WallStreetBets, fraternized through stories, stories of their major gains and major losses, often told with absurd memes and irreverent idiosyncrasies.

Of course, now that the GameStop stock play has come to a crashing end, it’s easy to dunk on inexperienced investors who took it for a ride. And to pan the press for perhaps blowing it out of proportion.

But ask yourself: Why do you do what you do? Why do you admire a specific person or associate with particular groups? Why do you follow certain routines? Why do you believe one thing but not another? Why do you buy the things you buy?

The same reason people opened Robinhood accounts this past couple weeks to start trading: A story.

Stories help us understand the world around us, pass along information and build relationships. When an unexpected event occurs – say, a group of retail investors fleecing some hedge funds – our desire for a cohesive narrative grows. We crave clarity, certitude and even identity through stories.

Research has shown that “compelling narratives cause oxytocin release and have the power to affect our attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors.” That is the same hormone released during labor, bonding mothers and newborn babies.

Wonder why people read tabloids? It’s like a textual dopamine hit.

A good story can make you rich (not just in a financial sense, but as in a life filled with joy). A good story can equally make you go broke (again, not just in a financial sense, but also broke in spirit).

Therefore, the power of the story is something we should all understand and respect. It can give us meaning and motivation. It can help turn the world in your favor (ex., convincing your boss for a raise). But, as many historical atrocities show, it can cause people to do terrible things.

I think the GameStop saga exemplified three major elements of an effective story. A good story may have one or all three. Knowing these elements can help you craft your own stories and keep you from falling victim to one.

1. Duality (good vs. evil)

Political propaganda is the apotheosis of this element, as it is used to define an enemy. As Aldous Huxley put it: “The propagandist’s purpose is to make one set of people forget that certain other sets of people are human.”

It’s good versus evil. The Rebel Alliance versus the Galactic Empire. The Lakers versus the Celtics. Or in the case of GameStop, the people versus Wall Street.

This dualistic storyline, of one thing in opposition to another, doesn’t always involve people. It can also take a more intangible form, such as the status quo versus a better future, which was the theme of Apple’s famous 1997 Think Different campaign.

But life is not so black and white; life is very gray. Therefore, any story presented in a dualistic framework – a sales pitch, a Trump fundraising email, an invitation to join a cult – is a good indication there’s more to the story than meets the eye. Be alert.

On the other hand, we don’t like ambiguity. We prefer simple either-or statements. So, for achieving a certain outcome – to earn approval for a work project, to attract investors in your start-up or to even adopt healthier habits – it’s easiest to change minds with a dualistic story.

2. A higher purpose

Gregor MacGregor was an 1800s fraudster who tricked British and French investors to invest in the fictional Central American country of Poyais. He conned investors with the story of a beautiful, civil and European-friendly territory ripe for opportunity. Part of his pitch to British aristocrats was that such an investment would not only be good for their financial health but also good for the strength of Britain and for the spirit of the Poyaisian people.

His story called to a higher purpose. Name it a theme or a motif, it’s what gives a story universal appeal.

GameStop was portrayed as a story about fairness and accountability, earning it references to the Occupy Wall Street movement.

But what is a story’s strength, is also its weakness. If the facts of the story don’t support its purported altruistic message, as in the case of GameStop, then you can tell the narrative is probably bullshit.

I’ve written before about the stories we tell ourselves. I am a diligent saver and I am an innovative entrepreneur are both positive stories, but they’re only effective if you have a reason why. No one saves money to save money. You should have a higher purpose as to why.

For example, why do you want to save and invest money? Those things aren’t meant to be done simply for the fun of it, but rather to serve a purpose. Once you have a specific purpose or goal in mind, you can work your way backward and come up with a plan to get there.

3. The reward

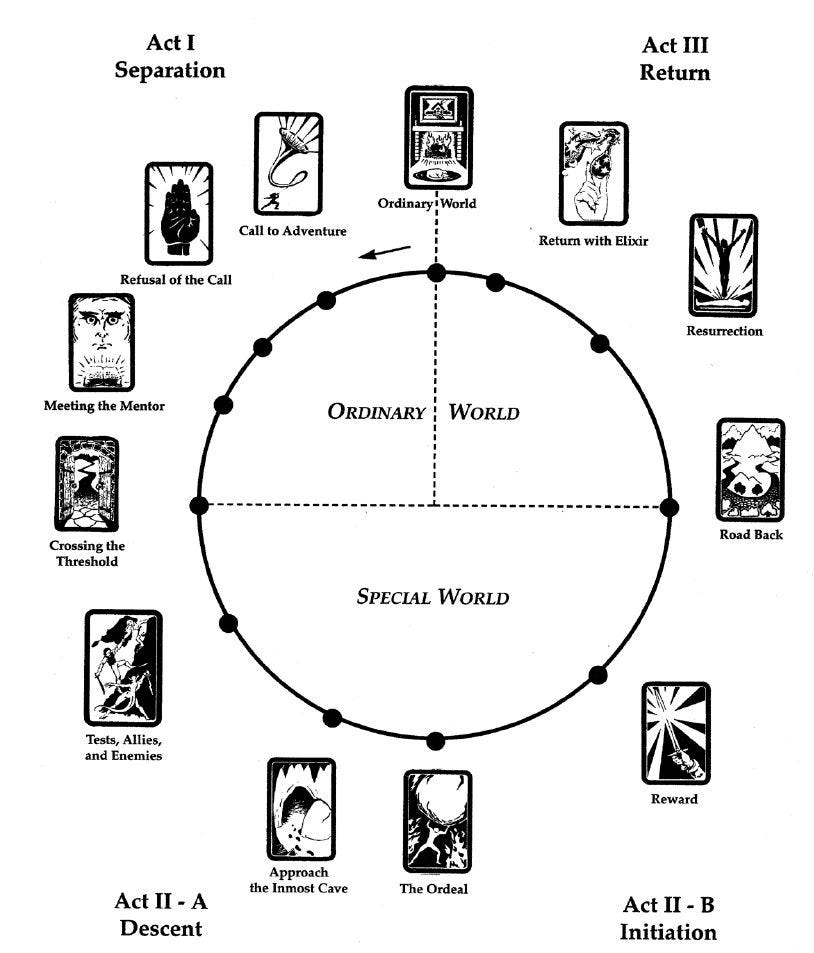

A common structure found among myths and folklore of many cultures is the Hero’s Journey, made famous by Joseph Campbell.[1] From the Odyssey to Star Wars, this storytelling model follows a character’s call to adventure and transformation into another world and back again, passing through different stages.

One of those stages is the reward, earned by the hero after overcoming a fear or slaying a dragon…

…or buying options on a cheap retail stock.

The GameStop myth follows this narrative arc: a call to adventure on Reddit, crossing into a special world (the stock market), slaying the titans of Wall Street and earning a reward of triple-digit returns.

Unfortunately, some of these heroes stayed too long in that special world, only to return to the ordinary world without their shirts.

The quest to achieve a reward that will transform your life is an alluring narrative, which advertisers know quite well. Deficit advertising is a marketing technique designed to make you feel as if something is missing in your life. Why do you need to buy that truck? Because your life is missing the excitement of a white-knuckle, adrenaline pumping joyride up a mountain.

For any reward, you have to give up something.

Imagining yourself on a journey is a helpful mindset when working toward a goal. The good thing is, especially when investing, you don’t need to make it a risky adventure. Investing money in a diversified portfolio for the long term is unlikely to be as exciting as day trading, but more likely to be rewarding. The real prize, however, may be all the mental and emotional energy saved by never having to make investing some kind of game.

So, what can we learn from the GameStop experience? Well, perhaps, it’s better to ask what stories are you listening to? Can you tell a better one?

[1] As I was writing this, Dave Nadig published this excellent article where he also notes the Hero’s Journey similarity as posited by Lily Francus.