Financial Writing with Empathy

If you want your writing to be more engaging, answer one question: Who am I writing for?

Berkshire Hathaway has legions of devoted shareholders, some of whom are quite famous -- LeBron James, George Lucas and Bill Gates, among them.

But when writing the annual shareholder letter, chairman and CEO Warren Buffett has only two people in mind: his sisters, Doris and Bertie.

As he said in an interview: "It’s 'Dear Doris and Bertie' at the start and then I take that off at the end."

Why? Because Buffett knows that his two sisters are not particularly active in the business and investing. They're not well versed on the workings and lingo of the industry. And he knows if he can connect with them, he can connect to anybody.

This targeted approach is a writing method Buffett uses to help refrain from using business jargon, and to make the letter more accessible and readable for wider audience of investors.

Most importantly, it is an act of empathy.

Empathy is the awareness of the feelings, thoughts and attitudes of other people. It is an understanding of what others are experiencing as if you were feeling it yourself.

When people think their feelings are being addressed in piece of content, they are more likely to engage. A study of advertising campaigns found that those with "purely emotional content performed twice as well as those with only rational content."

Empathy is the key to connecting with readers on that emotional level. It's the difference between speaking to someone and speaking with someone. It can help you and your writing stand out among the noise.

Considering how emotional financial decisions can be, empathy is a necessary feature of financial writing.

We all want to make rational financial decisions. What often gets in the way is our emotions. A financial blog or article can have all the right answers, but it will likely fall flat if it concentrates on the rational aspects -- analysis, statistics, rules, etc. -- while giving the emotional short shrift.

Mere information is rarely helpful unless it also directly relates to your life.

With empathy, your writing can show that you understand what the reader feels and thinks, that you share those feelings and that you want to help however you can.

How to make your financial writing more empathetic:

The good news is your desire to help other people make better financial decisions is proof you're an empathetic person. And showing it in your writing doesn't require special hacks. It's all about writing plainly and sounding like a human who shares the same goals as the reader.

Here's how to do it.

Humanize your language

Writing about things like balance sheets, taxes and investments can easily come off as stiff and academic. An easy step to humanize your language is to write in the first person. The personal and relatable touch of first person is more engaging than the formal tone of third person.

Let's compare.

Here is a typical corporate tagline in third person: "Acme Financial is a wealth management firm that provides personalized, honest and expert financial planning services."

Now, using the more friendly first person: "We'll help care for your financial needs with personalized advice that you can trust."

Don't be afraid to use empathetic words and phrases like "I understand how you feel", "You are in a tough spot" and "This must be really challenging for you".

Above all else, simply write as if you were having a conversation. If that means breaking some grammatical rules... Well... So, what?

Simplify the complex

With all the different products, rules and regulations, finance is often overly complex. Add in the desire to sound like an expert, it can lead financial writers to use industry-speak with terms like "asset allocation" and "tax-loss harvesting".

It can sound alien to average readers, leaving them confused or wanting.

So, show that you care by writing with short, simple and familiar words. And follow the Feynman technique: explain things in a way even a child could understand.

Further, emphasize what your readers really want.

You may be able to wax-poetic about a strategy for withdrawing 4% of a $1 million portfolio with a 99.9% probability of lasting for 30 years. But it may not resonate unless you explain how it will help retirees sleep at night and never fear running out of money.

Create your characters

Like Buffett, it helps to actively visualize the people you are writing to. If you don't know real people that match your target profile, that's okay. Make them up.

Research suggests that by mentally stepping into the shoes of fictional characters, we become more empathetic and socially-aware.

Create as much detail as you can -- names, ages, interests, even stock pictures. Whatever helps you form a relationship to those you want to reach most. Then write to them every time you write.

You have a message that could help people. All they want from you is to speak with them. Hopefully, this will help you do that.

Friday Five

Author Garth Greenwell writes beautifully on the role of relevance in art

Maybe this is just a kind of cheap mysticism, like a secularized treasury of grace—the old theological idea that there are certain substances, such as God’s love, that as they are spent do not diminish but multiply. Maybe what I’m suggesting is pure fantasy, imagining that our attention could be like the loaves and fishes at the feeding of the five thousand. Maybe that’s true. But maybe it’s also true that there are certain indefensible positions we must hold because not to hold them would be an affront to the human dignity necessary for any world in which we should rightly wish to live.

Marketing genius Seth Godin on playing to the masses or following your own path

You can either turn your operation into a cross between McDonald’s and Disney, selling the regular kind, pandering to the middle, putting everything in exactly the category they hoped for and challenging no expectations…

Or you can do the incredibly hard work of transgressing genres, challenging expectations and seeking out the few people who want to experience something that matters, instead of something that’s merely safe.

Growth always fights against competition that slows its rise. New ideas fight for attention, business models fight incumbents, constructing a building fights gravity. There’s always a headwind. But everyone gets out of the way of decline. Insiders might try to stop it, but it doesn’t attract masses of outsiders who rush in to push back in the other direction like progress does.

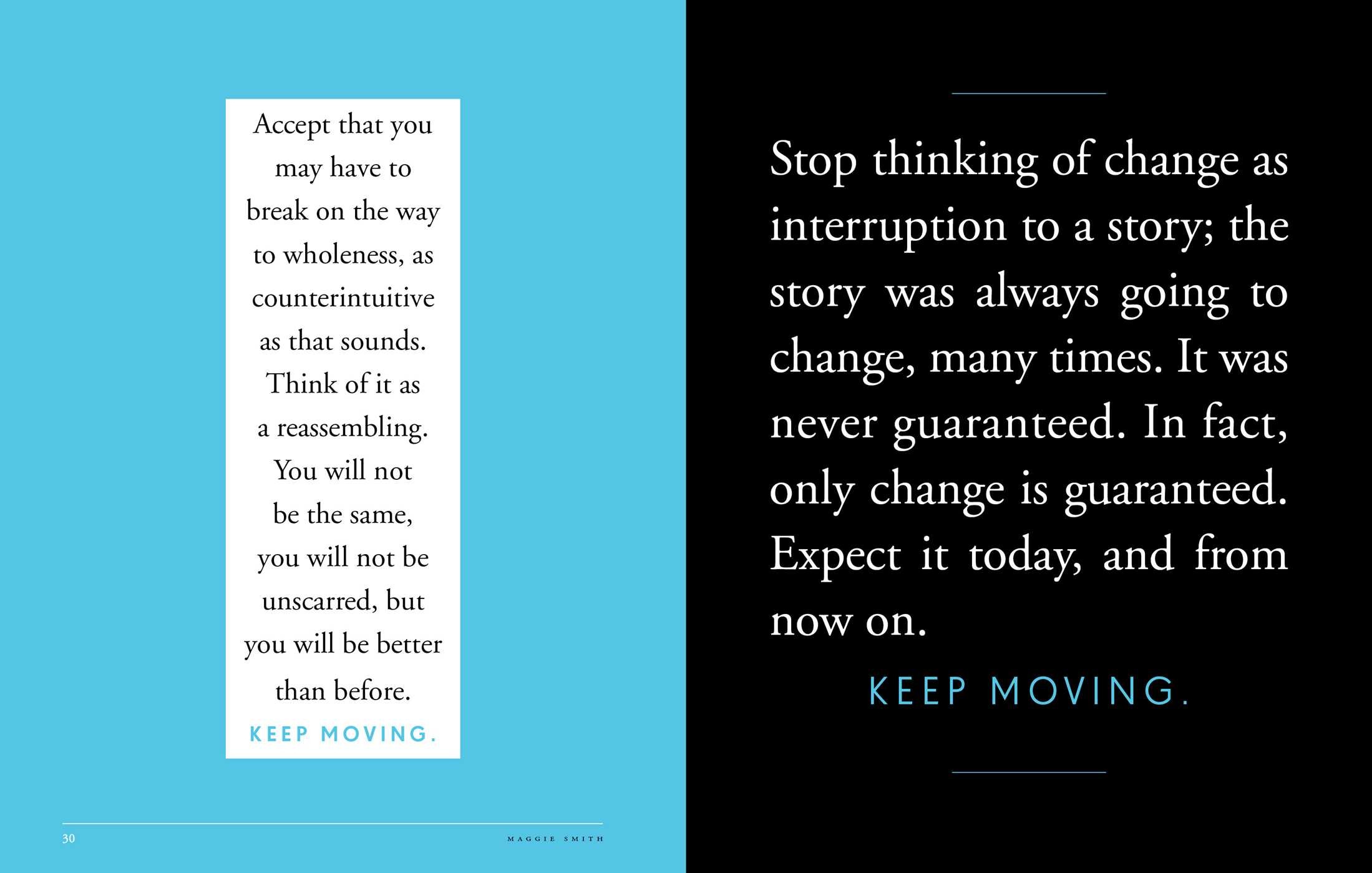

Friday (non) Fiction: Poet Maggie Smith's moving new book on grief and transformation