Cleaves of Capitalism

The business of coming between you and your money

Hi,

I want to give a sincere shout out to all of you who sent kind messages in response to my previous post. Thank you!

In this edition:

The art of making something unnecessary out of nothing

How to recognize and avoid the “dependence effect”

Running 500 miles in rubber boots if that makes you happy

It’s remarkable we’re even here, really.

After all, we’re born as small, helpless creatures — soft skull, rubber limbs, unable to crawl, roll over or feed ourselves.

A foal gets up and gets running. But a human must be carried, fed, turned, watched, prayed over. For years.

And still — somehow — here we are. You and me. Writer and reader. Two improbable survivors of thousands of years of improvised newborn care performed by sleep-deprived people with no YouTube tutorials, no parenting blogs, no cortisol-spiked threads of advice from strangers and certainly no chatbot glowing in the dark like a digital wise man.

But maybe we’ve been doing it all wrong.

Do we need artificial intelligence to raise a baby?

Depends on who you ask. For most people, the answer is likely an unequivocal no.

But there’s another group, growing more vocal, who seem to believe that humanity has been trudging through the desert of ignorance, and only recently, finally, have we been granted the sacred tool required to shepherd a newborn into adulthood.

Recently, on The Tonight Show, Jimmy Fallon asked OpenAI’s Sam Altman if he uses ChatGPT to help with parenting. And Altman, in that casually prophetic way of his, said: “I cannot imagine figuring out how to raise a newborn without ChatGPT.”

Sure, it being a comedy show, there’s a tinge of sarcasm here.

Still, “cannot imagine figuring out” is a strong way of putting it, as if our collective existence is not direct proof that it has been figured out — fiercely, tenderly, successfully — for a long time.

Parents everywhere, hearing this, might be expected to think: Have I been doing this wrong? When my baby screams so hard his lips turn blue, should I open a laptop instead of my arms? Should I trade the sweaty-forehead rocking rhythm — the ancient ritual that ends with both of us falling asleep in a heap of love and surrender — for a prompt box?

Sure, Sam, sure.

While the technology is new, the strategy is not. Altman is taking a page out of the old capitalist playbook. They say necessity is the mother of invention. But money is the midwife of unnecessary inventions.

If there’s one glaring flaw in the free market, it’s the shameless effort to convince people they suddenly can’t do the very things they’ve been doing easily for years. The message gets repeated until it sounds like truth: you don’t know anything and you can’t do this, all delivered through millions of marketing dollars and a parade of celebrity cameos.

As George Carlin, patron saint of calling BS, once said:

“Advertising sells you things you don’t need and can’t afford, that are overpriced and don’t work.

And they do it by exploiting your fears and insecurities.

And if you don’t have any, they’ll be glad to give you a few.”

Or, take it from a more fitting voice on the matter, Fight Club’s Tyler Durden:

Why Tyler Durden? Sometimes, personal finance is a combat sport.

Consider entrepreneur and writer Scott Galloway’s formula for wealth:

Wealth = Focus + (Stoicism x Time x Diversification)

Galloway says Stoicism is about “living an intentional, temperate life in and out of work.” Another way of putting it is not wasting money, time and energy on s**t you don’t need.

For various reasons, other people are going to try to muscle their way into your equation. So as part of building wealth – whether that means getting rich or simply having a secure life to pursue the things you enjoy – you’re gonna have to do a little fighting.

Because capitalism has a way of swinging an axe at the base of your certainty.

Beware the cleaves of capitalism

Big fan of capitalism here. It has irrefutably been a good thing, reducing poverty and creating opportunity for us to participate in the creation of wealth and new ideas.

But as with anything, there’s room for excess, and where there is no apparent room to make money, capitalism will find a way to make room.

A cleave is a split, a tear, a purposeful breaking-open of something whole. And capitalism is extraordinarily skilled at making tiny separations in your life, like a lumberjack tapping a wedge into a tree trunk.

A small gap becomes a crack.

A crack becomes a canyon.

And into that canyon: their product.

The economist John Kenneth Galbraith named the most elegant version of this trick the “dependence effect”:

The production of goods creates the wants that the goods are presumed to satisfy.

If a tree falls in the forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound? If the want had never been created, would we even know we were missing anything?

One of the most obvious examples is health supplements. There’s good reason to think they can help if you have some kind of natural deficiency or are training for a particular goal that requires high performance. Still, most nutrients are found in regular healthy food. And the greatest boost will be found in dialing in the basics, like consistent workouts, a balanced diet, adequate sleep.

Or speaking of babies, the commercialization of motherhood is everywhere. Studies on baby registries, toys and feeding gear show how parents are subtly told that more stuff = better, safer, more loving parenting.

The dependence effect thrives on unnoticed psychological nudges — fear appeals, social comparison, status cues, moralized language (“good parents do X”) and aspirational identity-building.

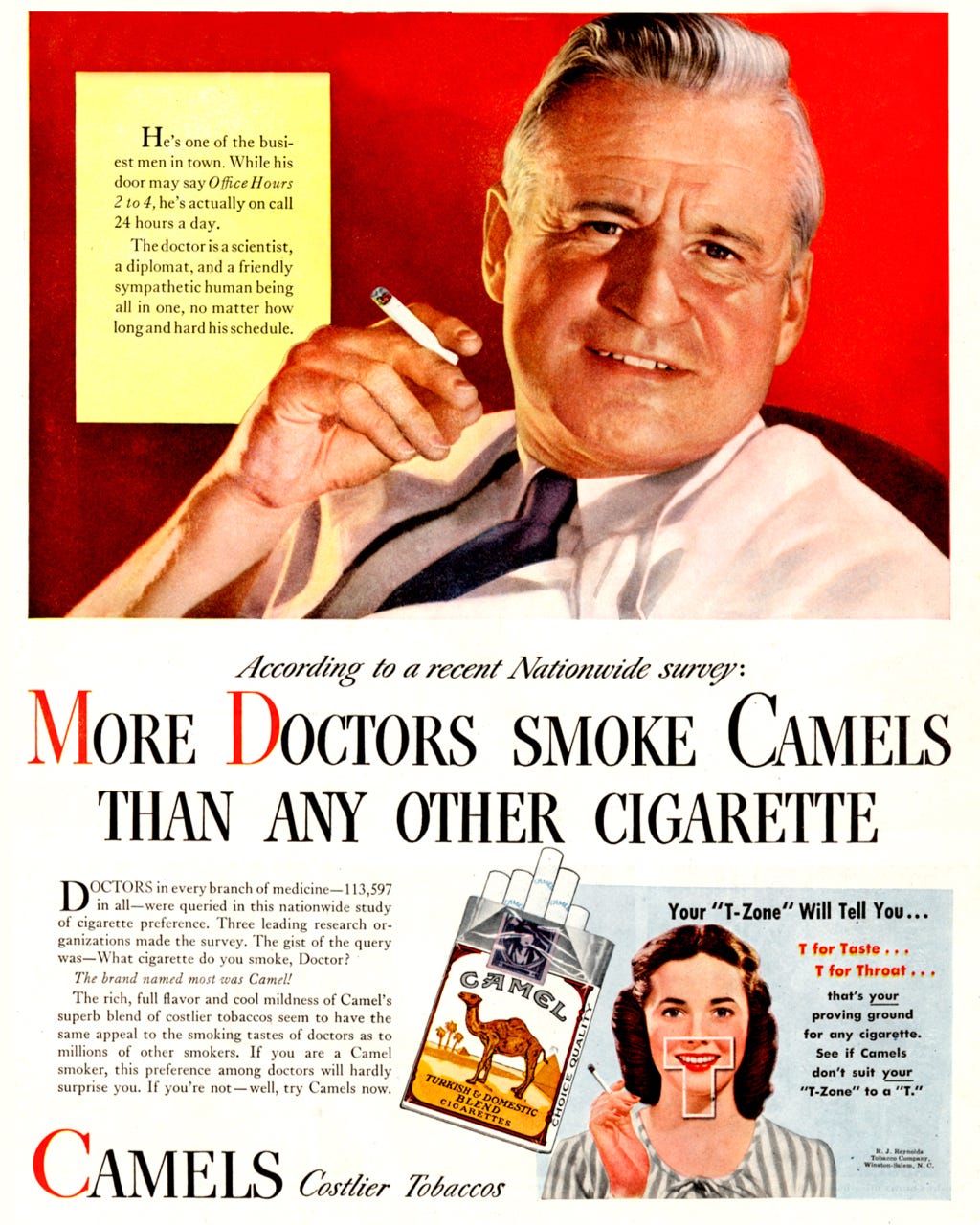

It’s the same system that brought you doctor-approved cigarettes:

Simply put: these little cuts make you buy what you don’t need and worry about what was never a threat.

Or worse, read the recent stories of people confessing they’ve begun outsourcing their thinking to AI.

I’d say this is oppostie to the wonders of life — awe, curiosity, growth. A fulfilling life means governing our own choices rather than letting someone or something else govern them for us.

Or, to Galloway’s point about Stoicism, take a page from Roman emperor and Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius:

“Almost nothing material is needed for a happy life, for he who has understood existence.”

That’s the intentional living and temperance that might matter even more during another boom in capitalism. It may require a stronger fight against that subtle separation, the wedge between what we want and what we’re told to want.

Filling the void with “no thanks”

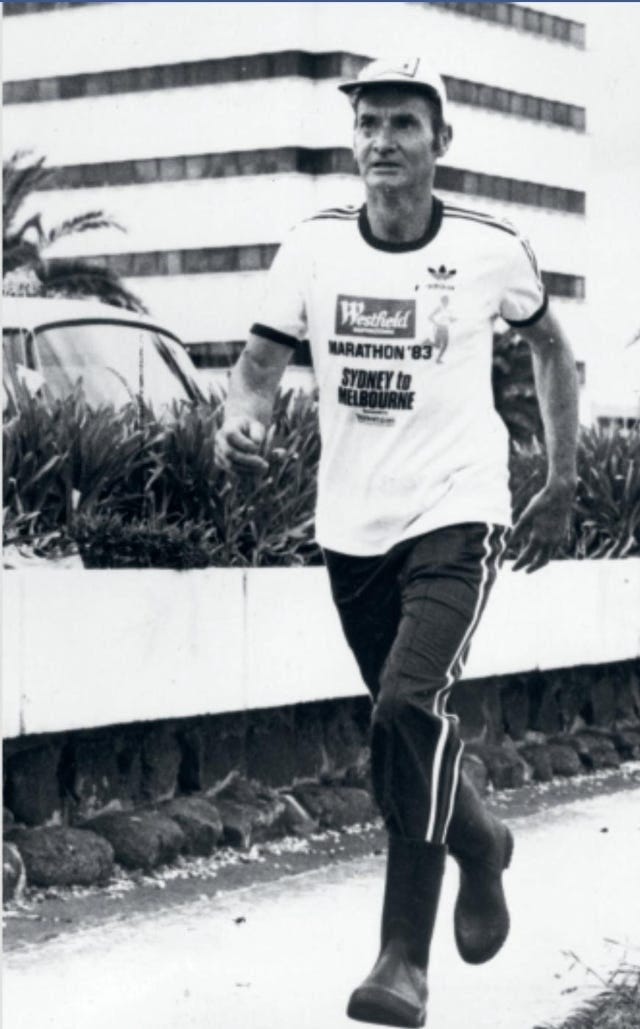

One day in 1983 Cliff Young just felt like running.

He was an Australian potato farmer who got into competitive running late in life. At the ripe age of 61 years old, he won the 544-mile Westfield Sydney to Melbourne Marathon.

Cliff cared only about running, which is why he’d often be found leading the pack dressed in the stuff he wore out in the field working, like rubber boots.

So, do you need “super shoes” to race a marathon?

It goes to show the power in what you can do without knowing what commercials tell you. I would not advise trying to race life Cliff. Better to have actual running gear. Yet, there is an inspiring power in what he possessed in the symbols of his rubber boots.

You can avoid the cleaves of capitalism by simply not letting them be put in you. Naming the tactic out loud weakens its power. Same with asking, Did I want this before they told me to? It can help shift from product-first thinking to need-first thinking.

It’s along the lines of what the writer David Foster Wallace meant when he said:

“[Be] aware enough to give yourself a choice.”

A cleave or a ditch is disrupted soil — something gone, removed. Sometimes that’s good soil. The fulfilling life, the one stitched with awe and curiosity, does not arrive through convenience alone. Some things — writing, carrying a baby, the slow ritual of making coffee — matter in ways no optimization can redeem. It may explain why some people see a boost in well-being when living a more simplistic lifestyle.

If wealth depends on controlling spending, then wisdom depends on resisting persuasion. Not puritanically. Not angrily. Just intentionally.

Life is hard. That unshakeable fact doesn’t make it a problem to be solved. So, when someone tells you can’t figure out a way, that there’s now a gap between you and what you’ve always done or really want, think long and hard.

Henry David Thoreau, clearing his throat from Walden, gives us the final note:

A man is rich in proportion to the number of things which he can afford to let alone.

That, perhaps, is the truest wealth in a capitalist society: the ability to walk back from the cliff, wallet intact, humanity unfractured, and say simply, “No thanks.”

Notes to my future self:

Beware the “dependence effect”: If I didn’t want it before they sold it to me, maybe I don’t need it.

Wealth is built by what you refuse, not what you acquire.

Not every hard thing in life is a problem; sometimes it’s the joy.

Until next time,

J.S.

On children: Sigmund Freud: I used to have six theories on raising children. Now, I have six children and no theories.

I doubt if AI can swallow that.