Arguably, the biggest factor in choosing to have children or not: money. So, what is the impact of children on your finances? Sure, kids are expensive, stressful, heartbreaking, unbearable and just overall pains in the ass… but as most parents know, you’ll get more in return than you could ever imagine.

Before reading, please do me the favor of subscribing if you haven’t. Right now, it’s free!

A subscriber asks: Why don't you post more frequently?

The answer is simple: Damn kids. Those damn kids.

As a father with two young hyperactive kids, it’s my response to nearly everything. Damn kids is what I say under my breath when I step on an errant LEGO, when I discover stains on the sofa, when I look at the grocery bill or when it just feels like I live in an UFC octagon.

It’s also my explanation for things delayed or undone, filed away in the drawer of unlived aspirations. There are moments when the writing muse arrives and the words flow like a river, until suddenly the gentle silence of an early productive morning is broken by the locomotive rumble of four clumsy feet down the stairs and – poof! – the magic is gone. Then I mouth my two-word phrase: Damn kids.

Sometimes I feel jealous reading great pieces by writers who have no children, shamelessly convincing myself that that is the only difference between me and them. But then I remind myself it’s just my insecure ego making excuses. Because the truth is that I want to be there for every game and practice, every meal, every homework assignment I can’t even understand, all the impromptu wrestling matches on the living room floor, each throw in the front yard until the sun sets behind the trees, and everything else that keeps my butt out of the chair and my fingers from dancing on a keyboard in solitude.

And there’s a price to be paid for that. The question for any would-be parent is: are you able and willing to pay it?

Before becoming a bestselling author, Michael Chabon was at a literary dinner when an older, well-known author offered some advice for becoming a successful writer:

“Don’t have children. That’s it. Do not.”

Essentially, this famous writer warned that kids would take time away from writing and keep you from experiences worth writing about. He continued: “You can write great books or you can have kids.”

In an essay about this encounter years later, Chabon wrote that he had gone on to write 14 books and doesn’t miss any that he may have sacrificed at the expense of having four children. That’s because: “[M]y books, unlike my children, do not love me back… if, 100 years hence, those books lie moldering and forgotten, I'll never know. That's the problem, in the end, with putting all your chips on posterity: You never stick around long enough to enjoy it.”

However, the older famous writer’s attitude is pretty common. The prevailing perception is that having children means losing something – a loss of identity, a loss of possibility, a loss of financial security. It leads many young adults to forgo having children at all.

A Pew Research Center survey found a growing number of childless adults say they are unlikely to ever have children. The majority of them say “they just don’t want to”. Why? In a similar survey by the New York Times, adults ages 20 - 45 cited many financial reasons for not wanting or not being sure they wanted children, including the cost of child care, worries about the economy, the affordability of more children and financial instability.

Children will change your life in many ways, and money seems to play a role in it all. So, it is certainly reasonable to consider the financial costs before starting a family. But do children make as big of an impact on our finances as we think?

Oh, by the way, the subscriber who asked the question, well, it was my wife. For us, having kids has been an ongoing adjustment. Our needs and wants change, and our finances change with them. Sometimes we think we need more, sometimes less. We don’t have a plan, as much as we are continuously planning.

Hence, I am personally curious about the financial impact of children, too. Let’s then dig into some of the data that explores the relationship between children and money… actually, one of the kids has just started crying in the other room, so why don’t you just go ahead.

Kids can be expensive – very expensive

Brace yourselves: The cost of raising a child to the age of 17 is more than $230,000, according to a report by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (that’s excluding college expenses!). Adjusted for inflation, that’s probably around $270,000 today. A cool quarter of a million dollars or so to make a loud, drooling, pooping machine become a taller, more functional loud, drooling, pooping machine.

Of course, the sticker price of a child varies based on factors such as location, family income and lifestyle, and special needs.

A substantial cost for most families around the world is child care. In America, the average annual cost of child care is more than $10,000, according to the advocacy organization Child Care Aware. In some regions, the cost of child care exceeds other big ticket items like housing, college tuition and transportation.

Child care is why many parents, often women, leave the workforce. In countries that offer generous child care assistance, this is much less of an issue (a theme of this post).

Still, the cost of raising a child is a challenge for even high-income earning parents. We all set high expectations for what we think we need to provide for our kids. And, maybe that is where many parents go wrong. We try to spend money – extracurricular activities, the latest gadgets, the top 1% schools – to foster healthy children rather than spend the time to raise them.

Whereas “Dear Abby” columnist Abigail van Buren advised:

“If you want your children to turn out well, spend twice as much time with them, and half as much money.”

I feel fortunate to have the financial means to pay for basic necessities but not for the best of everything else. It compels us to spend time with our children and within our community, participating in free activities. So, we essentially grow closer to both our children and community as a way to lower costs, which in its own way is worth a lot.

Fathers may earn more than their single peers… but childless couples have more wealth

Although the cost of raising a child is high, you can expect to earn more… if you’re a man.

Research from the City University of New York found that men with children earned more money than both their childless peers and women with or without children.

This could be the result of men working harder and putting in longer hours to support their families. Or, employers may have a bias toward fathers, viewing them as warmer and more devoted employees.

But, fellas, it’s not enough. Overall, childless couples come out ahead financially. Despite fathers earning higher incomes, an 2014 Urban Institute report shows that families with children tend to have lower incomes than families without children. The median income for families with children was about $62,000, compared with about $68,000 for families without children. While men’s earnings increase after fatherhood, women with children have lower average earnings than women without children (more on that later…).

This wealth disparity carries forward as a Census Bureau report found older childless couples reported higher levels of personal net worth and educational attainment than older parents.

The major reason why, again, is child care. Research from the Center for American Progress says a parent can expect to lose up to three or four times their annual salary for each year out of the workforce.

This goes to show children may force you to reorient your life. Even someone in the arts, like the author Chabon mentioned above who said having children made him stop writing short stories. Not because he no longer had the time but rather because short stories don’t make the kind of money books do. Children are expensive and he simply couldn’t afford to write short stories. And, it worked out quite well for him.

So, the transition from preparental to parental life doesn’t have to be negative. People often struggle with the loss of their preparental identity while trying to at the same time rejoice in their children. But maybe what’s really happening is that you’re gaining a new, more refined identity.

Sure, in the worst moments, I wish to carbonize my children like Han Solo. Yet, when I think back to my life before children, there was a lot of wasted time. Once I had kids, I gained a greater appreciation for the impermanence of life. My sense of self was no longer defined by career success or failure. With children, you might discover what really matters most to you, and you might chase those priorities with greater urgency and less worry about failing.

It brings to mind the poem “air and light and time and space” by Charles Bukowski who writes:

if you’re going to create, you’re going to create whether you work 16 hours a day in a coal mine, or you’re going to create in a small room with 3 children while you’re on welfare

If nothing else, parents are often paid back later in life. The Census Bureau reports that childless older adults have fewer sources of potential support within their households. About 4 in 10 childless older adults live alone, compared to 2 in 10 parents. More wealth or time isn’t always worth much when you’re alone.

Most of the burden – financial and physical – of raising children falls on the *tired* shoulders of women

It’s not easy being a mother.

Women are disproportionately impacted by children. In every country, women earn less than men. Take the United States, where women earn 79% of what men do.

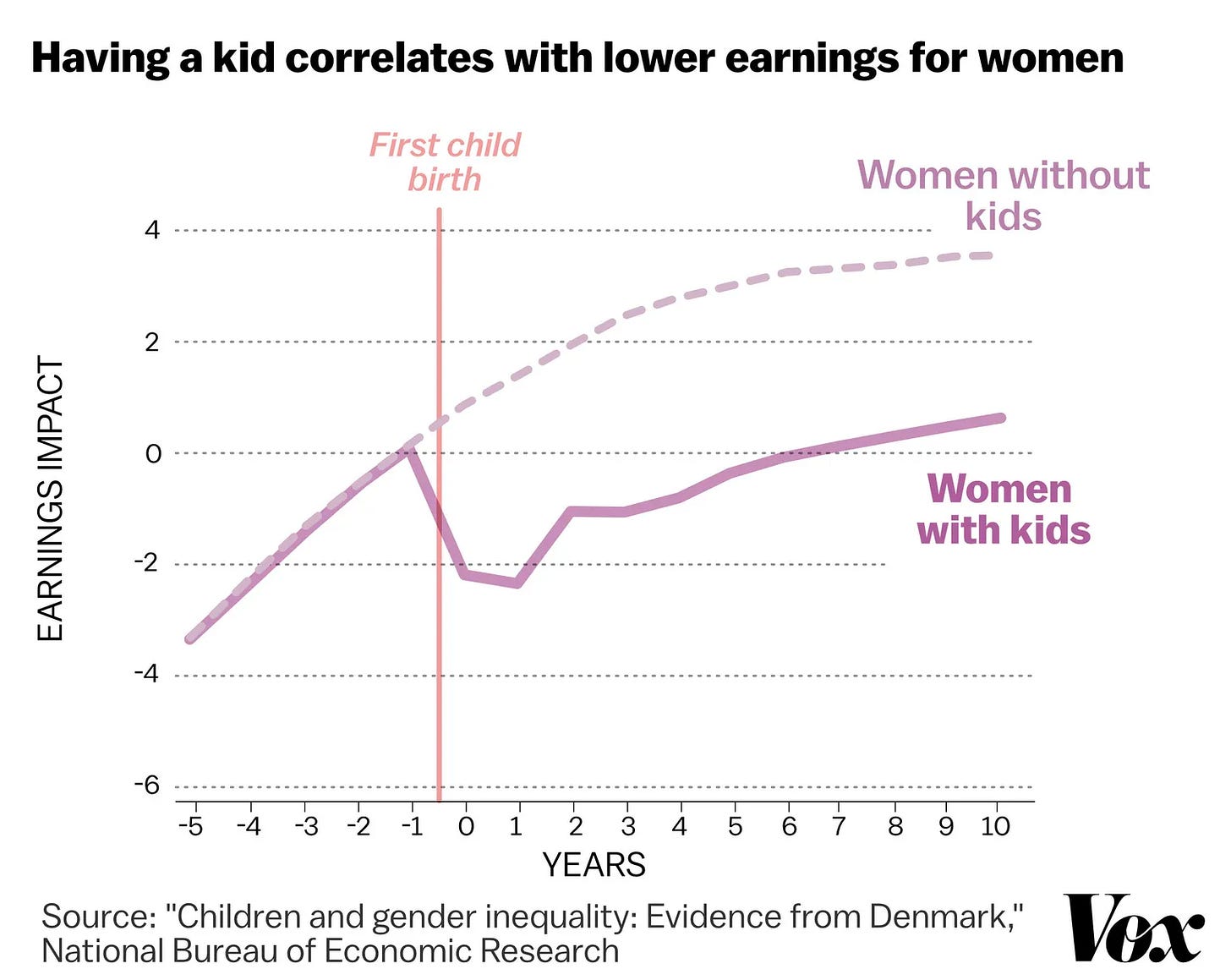

A Princeton University study, as reported by Vox, suggests this wage gap is the result of having children. The study looked at workers in Denmark, a country that provides substantially more in child care support but similar wages as the U.S. Despite that, women experience a sharp decline in earnings after the birth of their first child. Men don’t. The disparity compounds as women earn 20% less than men over the course of their careers.

The decline in earnings after the birth of a child also leads to vastly different earnings trajectories between mothers and women without kids.

What’s worse – yes, it can get worse – when women do earn more than their male counterparts, they are not necessarily rewarded at home. A study published in the journal Work, Employment and Society says mothers who earn more money than their husbands actually do more housework. In the study, women with children whose earnings went from zero to half of the household income saw their housework drop from 18 to 14 hours a week. But once a mother started earning more than her husband, her housework jumped to nearly 16 hours a week. Housework for a father ranged from six to eight hours a week when earning most of the household income, but it then declined as his wife became the primary breadwinner.

We can better see the impact of child care on women’s finances when comparing single mothers. A survey of more than 2,000 women shows single mothers who share parenting duties with fathers evenly tend to earn more money. In fact, single mothers who share parenting were more than three times more likely to earn $100,000 than single mothers who are with their kids 100% of the time.

Further, single mothers with 50/50 parenting were 34% more likely to say they feel “awesome and proud” of being a mom compared to those caring for their kids 100% of the time.

The writer Rachel Cusk unpacks the hard truth of life as a mother in her memoir A Life’s Work: On Becoming a Mother:

To be a mother I must leave the telephone unanswered, work undone, arrangements unmet. To be myself I must let the baby cry, must forestall her hunger or leave her for evenings out, must forget her in order to think about other things. To succeed in being one means to fail at being the other. . . I never feel myself to have progressed beyond this division. I merely learn to legislate for two states, and to secure the border between them. At first, though, I am driven to work at the newer of the two skills, which is motherhood; and it is with a shock that I see, like a plummeting stock market, the resulting plunge in my own significance.

Taking her financial metaphor forward: in many countries it’s as if the central bank artificially raises rates on motherhood to keep women in a perpetual bear market. The remedy requires systematic changes to support mothers, whether pregnancies are planned or not. They say it takes a village to raise a child. At the very least, men could provide an extra pair of hands at home.

Deep breaths: Parents experience higher levels of financial stress than nonparents

Turns out those “bundles of joy” are stressful. An American Psychological Association survey found parents of children under the age of 18 are more likely than adults with no children to have higher levels of financial stress and are less likely to feel financially secure.

Again, it’s no surprise considering the various financial costs of raising children – diapers, day care, toys, sports, wine for when they finally go to sleep. It explains why some research indicates parents are less happy than nonparents. A 2016 paper reports this happiness gap appears in most advanced industrialized societies, with the widest margin in the United States. Its authors say countries with “more generous family policies, particularly paid time off and childcare subsidies, are associated with smaller disparities in happiness between parents and non-parents.”

Or, maybe parents are actually happier. The responsibility, commitment and sacrifice involved is why conflicting research shows that parents feel happier, a greater sense of meaning and less sadness than nonparents. That’s according to a paper from the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research. It finds parents experience more positive emotions than nonparents during common daily activities, such as working, doing housework and leisure time. However, parents also feel more stress and fatigue.

A study published in the Journal of Positive Psychology came to a similar conclusion. As people spent more time taking care of children, the more they said their life was meaningful though not happier.

Further, researchers from Princeton University and Stony Brook University found that life satisfaction is about the same between parents and nonparents. The difference is that parents report higher levels of joy and stress each day than nonparents.

Studies on the differences in happiness between parents and nonparents come to varying conclusions. Raising children may then have a fluctuating impact on happiness but a more lasting influence on other elements of a what we’d call a fulfilling life – meaning, purpose, love, connection. The trouble is that the good and the bad can manifest themselves at any given time.

Sometimes they all occur in a single hour. Say, you buy a crib from IKEA and you feel joyful that this beautiful piece of craftsmanship will support the delicate head of your newborn, but you can’t for your life decipher the illegible instructions so that after attaching every piece and screwing every screw it looks more like a bookcase than a crib, making you question whether it’s good enough for your precious child, and then you start to evaluate your own self-worth as a parent until you’re lying in the fetal position in the corner of the nursery sucking on your own thumb. Not that that has ever happened to me or anything.

What I’m saying is that parenthood is bittersweet. It can be both stressful and enjoyable. The paradox seems to bend time and space. You will even miss the bad days with your children when time goes by so fast.

As the author Gretchen Rubin wrote:

"[Parenthood]: the days are long, but the years are short."

When our boys were toddlers, we took them on a boat tour on Lake Michigan while on vacation. They were extremely overtired. They wouldn’t stop crying and refused to sit still or keep their life jackets on. The frustration was palpable on our faces. Thankfully, a few older women on board came and sat by us to help soothe them. I’ll never forget one who said: “I know this is difficult, but please try to enjoy it. My kids are all grown and there’s nothing I wouldn’t give up to go back to where you are now.”

When things get stressful, I try to remind myself that one day the house will be still and I’ll have more time to write and more money to spend on myself – and I won't want it that way.

Monkey see, monkey spend: Children adopt financial habits from their parents

If any parents need additional motivation for keeping their finances in check, consider that financial habits can pass on from one generation to the next.

Behavioral researchers from Cambridge University say that kids start learning about money as young as age three, and most of their attitudes and feelings about money are formed by age seven. Meanwhile, a Journal of Economic Psychology paper suggests that parents’ financial behaviors and attitudes towards money, from talking to kids about money to showing delayed gratification, influence their children’s financial behavior all the way into adulthood.

This is a testament to the importance of teaching children about money, whether it is through an allowance, setting up a lemonade stand or involving them in financial decisions. The cumulative effect is why money should never be a taboo household topic.

Take it from Abraham Lincoln:

“Teach the children so it won't be necessary to teach the adults.”

Talking about money doesn’t have to only cover budgeting, saving or spending. It can also be a discussion about what you value or find most meaningful in life.

In that sense, I’ve learned some important financial lessons from my kids. One being that spending money is not a necessity for finding joy or for supporting the things you value. Because our most special memories have been the spontaneous moments and not the deliberate, costly moments – the Nerf wars, not the Disney World stores.

That can be true for anyone, kids or not.

Many parents provide financial support to adult children

If a child flies the nest but still gets money, is the nest ever empty?

Turns out, many parents choose to keep their doors and their wallets open. Nearly 40% of empty nesters are still supporting their adult children financially in some way, according to a report by 55places. The average monthly amount these parents spend on each child is $254, going toward everything from cell phone bills to groceries.

Typically, by the time children reach adulthood, parents are on the backend of their careers and nearing retirement, a time when you’re living off your savings for the rest of your life. Too much financial support given to children for too long can lead to increased levels of anxiety and physical ailments due to financial stress, as well as dramatic lifestyle changes.

Therefore, financial support to adult children can be a risk. Though I don’t think anyone can rightfully judge parents who struggle to financially cut off their children. After all, even in the richest country in the world, fewer Americans are outearning their parents – more or less shattering a piece of the American Dream.

Still, unless a child is in trouble, ongoing financial support can turn into enablement. Bill Gates, when explaining why he isn’t leaving most of his vast fortune to his children, said: “It’s not a favor to kids to have them have huge sums of wealth. It distorts anything they might do, creating their own path.”

Warren Buffet concurs:

I still believe in the philosophy … that a very rich person should leave his kids enough to do anything but not enough to do nothing.”

Even if they’re not giving money to their children, empty nesters tend to spend rather than save. According to researchers at Boston College’s Center for Retirement Research: “Households do not increase their savings very much even when the kids leave home.” Empty nesters on average increase their savings in 401(k)s only by slightly less than 1% of their income more than eight years after their child moves out.

I can imagine an empty house is a major life event, one that is fraught with both feelings of celebration and loss. The desire to live it up again versus holding on to what is now gone. Maybe some older parents give money to their adult children as a way to fill the empty space in their lives and hearts, a space once occupied by a chubby, snot-nosed, loveable face.

Life with children is sadly short. As every parent knows – both young and old – the time runs out faster than the cash. It’s a fact of life once pondered by the philosopher Seneca, who mused:

“So you must match time’s swiftness with your speed in using it, and you must drink quickly as though from a rapid stream that will not always flow.”

Coda

So, are kids worth the cost?

Ultimately, most countries need more affordable child care services, better public assistance, partners who do their share, and accessible financial planning services for families of all economic situations. Absent all that, it should be no surprise when young adults choose not to start families.

Kids are expensive. They cost a lot of money, time and energy. So, I understand why people voluntarily don’t have kids. But, I would never choose a life without them. Among the threads of infinite multiverses, I would never want to explore any other life without children. In my experience, as discussed in some of the sections above, children have given as much to me as I have given to them.

The cost of children is an admission to adventure, love, pain, joy, despair, loss, fulfillment – all that life can and should be. Then one day it’s over. The ride comes to a stop – hopefully, much later than sooner – and that emptiness is a bittersweet debt. It is a debt that can never be repaid. You are left desperately wishing to repay it only to take it out again so you can relive it all over, desperately wishing to take out a second mortgage on all the spills, the cuts and bruises, the breaks, the heartaches, the tears, the smiles, the hugs, the laughs, the I love yous and the goodbyes, enough to get you angry at the unfairness of it all.

Damn kids.

Take a Penny, Leave a Penny

Links to various things I enjoyed recently. Feel free to share with me what you’ve been reading (rootofall@substack.com).

How to Vacation With Kids While Broke

Speaking of kids and money, here’s a great personal essay on the joys of traveling with kids cheaply.

What I love about broke travel is that the good parts are really good — the highs feel extra high, because they represent the overcoming of some very present lows. Most of our built environment is organized around extracting money from us and making us feel bad if we can’t afford things; breaking free of that cage, even briefly, feels like being truly alive.

Mary Gaitskill is a legendary writer I admire. Here she shares some secrets of what makes for good writing.

Unless you are a surgeon or are the witness to a horrible accident, you aren’t going to see the guts of the body, but if you touch the person you will feel them beating under your hand—on a hot day you might even smell them. But smell them and feel them or not, they are what is holding the body up. The unconscious and the viscera; each is a fundamental force behind the person you look at. Something comparable to that fundamental inner quality or qualities are what make a piece of writing alive or not. These inner qualities determine what the work is about as much as the plot or the theme or even the characters. Strangely, writers themselves sometimes don’t know what this inner force is in their own work because it is so entwined with our own way of seeing, we barely notice it, any more than we notice our own breath.

On the Inevitability of Bear Markets

Some investors believe that when markets go crazy, active investors will rise to the occasion and successfully take advantage of every abnormality. I don’t believe that. But I do believe in those times, some financial thinkers will rise to the occasion to become a valuable source of wisdom, such as Ben Carlson, who has been posting insight after insight breaking down the craziness of 2022.

The point is not to predict every bear market or crash, but to psychologically prepare for them ahead of time. Knowing this event can and will occur is half the battle because you will set up your investment plan to take it into consideration. The long term is inclusive of market losses. Prepare yourself and act accordingly.

Your Moment of Grace

“Generous listening is powered by curiosity, a virtue we can invite and nurture in ourselves to render it instinctive. It involves a kind of vulnerability— a willingness to be surprised, to let go of assumptions and take in ambiguity. The listener wants to understand the humanity behind the words of the other, and patiently summons one’s own best self and one’s own best words and questions.”

-Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise: An Inquiry into the Mystery and Art of Living

I love to read your articles - I do not care for the use of profanity - I am no religious nut at all just think profanity has no place in public writing - I never use profanity but I am not perfect by any means - I do have human weaknesses - I really really liked the Art of Money!!!! Very well written - Looking forward to more insights from your work - thanks

As a soon to be father, this was an incredible read and I thank you for writing it